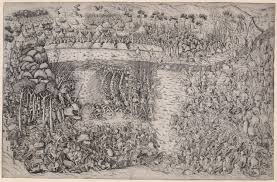

The Battle of Fornovo

In the late 15th century, French monarch Charles VIII standardized and increased the mobility of his siege cannon and ushered in a true revolution in military affairs. No medieval castle could withstand his guns. He seized castles “in the time it took to seize a villa.” In 1494, at the behest of Milan and Venice, Charles blitzed down the Italian peninsula to press his claim to the Kingdom of Naples, which he successfully took in February 1495. The Middle Ages came to a close.

Charles VIII’s 1494 campaign horrified the Italians. No one had traversed the length of the Italian peninsula as quickly since Hannibal crossed the Alps. During the Renaissance, the Italian boot consisted of dozens of super rich merchant republics, prosperous petty kingdoms, independent city-states, Papal States, and ultra-wealthy families, who vied with each other for political power. If an outside force intervened, such as Spain, the Holy Roman Empire, or France, the invader was usually fixed at fortress cities in northern Italy. While they sat outside the walls of Milan, Florence, or Mantua, the Italian petty rulers had time to buy them off, hire mercenaries known as condottieri (literally: “contractors”) to discourage any advance, or work political angles to turn back the invaders. Or they could just wait for the cold, muddy, and miserable Italian winters to break the will of even the most resilient invader. Charles VIII changed all that, and the Italians concluded they had to defeat him, lest he conquer them all with his cannon.

Charles’ erstwhile allies were the first to recognize the danger. The Sforza’s of Milan saw no reason for Charles not to seize their city on his way back to France. The Merchants of Venice knew they were next if Milan fell to the French. Pope Alexander VI, born Rodrigo de Borja, had already been defeated by Charles and forced to flee Rome. He put his considerable diplomatic and political skills to work. Not that much incentive was needed, everyone saw what Charles’ troops, particularly his Swiss mercenaries, were capable of. Any town that offered resistance was massacred, looted, and put to the torch. In March 1495, Alexander VI formed the Holy League with Venice, Milan, Ferdinand of Aragon and Sicily, most of the northern Italian city-states, and Emperor Maximillian I of the Holy Roman Empire to oppose the French.

Naples wasn’t worth being trapped there, so Charles gathered his army and immediately departed for France. His army was wracked with syphilis (brought back by Neapolitan sailors of Columbus’ expedition to the New World and subsequently passed onto the city’s prostitutes, and then to the French), heavily laden with booty, and although his cannon were effective against walls, they were not as effective in a field battle. Furthermore the longer Charles delayed, the stronger the Italian army grew. And, even worse, it looked as if the Italians meant to fight.

The Holy League chose famed condottiero Francesco II Gonzaga, the Marquis of Mantua, then in Venetian employ, to lead the League’s army against Charles, at least in theory. In reality, the League’s army was actually controlled by Francesco’s uncle Rodolpho, the commander of the army’s reserve, and led by committee, with the Venetian Senate the most influential.

The squabbling among the League’s members continued until Charles’ army reached Florence, and even then Francesco wouldn’t move until he had nearly a 3 to 1 superiority over the French. Charles had no idea how large the League’s army was or even where it was: his spies were forced into hiding, and his efforts at reconnaissance thwarted by the League’s stradioti, fearsome light cavalry recruited from the Balkans. When Parma threatened to side with the approaching Charles, the League’s army finally advanced. Just south of Parma, the League’s army encamped around the village of Fornovo on the right bank of the Taro River to wait for Charles.

As Charles approached Parma from the south on the road paralleling the right bank of the Taro River, he stopped as soon as he came into contact with the League’s army. He waited for a few days for news of a French army in the vicinity of Milan, and Francesco obliged him. On 5 July, 1495, Charles learned no reinforcements were coming, and decided to bypass his adversaries.

On the morning of 6 July 1495, Charles nonchalantly continued negotiations with the condottieri heavy Italian army, while his own crossed over the shallow Taro River to the left bank and proceeded north. The maneuver took the Italians by surprise, as normally no further movement was permitted until pre-battle negotiations were concluded. By the time the Italians reacted, they were forced to attack across the river to reach the French. The river was swollen, and the fords limited which effectively neutralized the League’s greater numbers. Charles didn’t want to fight a battle in any case: he planned for his vanguard to fix the Italians in their camp, while the rest continued to Parma following the left bank north.

Charles’ vanguard consisted of the best troops in the army: his cannon, Swiss halberdiers, and the Gendarme, the heavily armed and armored noble French knights. His cannon shrugged off the obsolete Italian cannons’ volleys from across the river and pummeled the League’s camp. The Italians hastily form battlelines at the river’s edge, and searched for fords. Unfortunately for the French, the stradioti and other Italian light cavalry raced upstream, and more importantly, downstream to cross were the French crossed that morning. They fell upon the heavily laden but lightly guarded baggage train, ponderously attempting to keep up with the fighting troops. The League’s light cavalry slaughtered the guards and spent the day looting, taking them out of the battle.

Charles could not react because the Italian right wing found a ford and attacked the vanguard, while he watched the League’s massive center battle attempt to find a suitable place to cross. The League’s right wing however could only cross piecemeal, and they were defeated in detail: the Italian knights were torn apart by Swiss halberds, and then the Italian infantry was run down by the Gendarme.

The center force, which was supposed to attack simultaneously with the north, finally crossed, and the battle engaged in earnest. However, they took too long to find a ford, and the French were prepared for them. Though the fighting was fierce, the issue wasn’t really in doubt: the superior cohesion of the French units overcame the disorganized Italians, many of whom deserted to go loot the French baggage train. The League’s only real chance at victory was when Charles was briefly vulnerable and exposed on the battlefield. However, the opportunity was missed by Francesco and passed quickly. His failure to capture the enemy commander was just another example of Francesco acting less the army commander and more of a unit commander. Despite the losses in the north, center, and baggage train, he still had numerical superiority, but he didn’t know it since he was so consumed with the fighting. A strong reserve, nearly half of the army, was still on the right bank uncommitted. Francesco was only entrusted with half the army; the other half belonged to Rodolpho, the commander of the “reserve”.

Disaster struck when Rodolpho was killed. As commander of the reserve, no one else had authority to order the reserve into battle, even Francesco. Thus nearly half of Francesco’s army never saw fighting that day.

The French pushed the Italians back to the river and gave no quarter. With no support from the reserve, a river behind them, and certain death in a losing battle, the Italian condottieri called it a day. They withdrew to the fords, then across the river and back to camp.

The French recovered what was left of the baggage train and continued on their trek, leaving the Holy League in possession of the field.

Despite the French successes, Francesco declared the Battle of Fornovo a great victory for the Holy League, and initially there was much jubilation in Venice and Rome. Not only had the French “fled” the field, but 300,000 ducats worth of booty was looted from Charles’ baggage train. After a few days though, Francesco Gonzaga’s condottieri competition began evaluating the battle with professional, calculating, and sober eyes.

The Holy League outnumbered the French nearly three to one, but took nearly three times the casualties as the French. The loot was good, but the purpose of the army was to prevent Charles from escaping to France, where he can raise an even bigger army to return. Gonzaga utterly failed in that objective. Moreover, his personal battle command was found wanting since he acted as a field officer instead of the commander of a great army. He was blamed for the looting of the baggage train which siphoned much needed troops away from the battle. He was blamed for the death of his uncle, and not committing the reserve. In the eyes of his peers, Francesco Gonzaga’s personal conduct had allowed the French to defeat the Holy League and escape.

Charles VIII of France did not return with a larger army, French debts prevented him from rebuilding the army he almost lost. Spain retook Naples shortly thereafter. He wouldn’t get another chance to return to Italy, Charles VIII died 2 ½ years after his retreat. He accidentally knocked his head on a door frame, fell into a coma, and never woke up.

Charles’ death was not the end of the troubles for the Italians. In fact, they had just started. Thousands of French, Swiss, and German soldiers and mercenaries returned home with stories of a weak, prosperous, and divided Italy, ripe for plunder and conquest. The myth of the fighting ability of the Italian condottieri died on the banks of the Taro. It seemed as if the condottieri would rather negotiate than fight, retreat at the first sign of difficulty, withdraw at the slightest disadvantage, and would not attack unless they had overwhelming odds. The command of any condottieri army would always be fragmented. The condottieri’s northern adversaries no longer respected them. Their Roman legacy was lost and the condottieri’s professional reputation was forever tarnished.

After the Battle of Fornovo, France, Spain, the Holy Roman Empire, even the Ottoman Empire salivated over potential Italian conquests and loot. They ended the Italian Renaissance and ravaged the Italian boot for the next 75 years, a time known collectively as the Italian Wars

You must be logged in to post a comment.