Tagged: WWII

The Naval Battle of Crete

The Aegean Sea belonged to the Luftwaffe by day, but the nights to the Royal Navy. Admiral Cunningham had two battleships, and three cruiser squadrons and two independent destroyer squadrons (about 40 warships) prowling the seas around Crete. They were searching for the dreaded German invasion fleet. On the night of 21/22 May 1941, they found it.

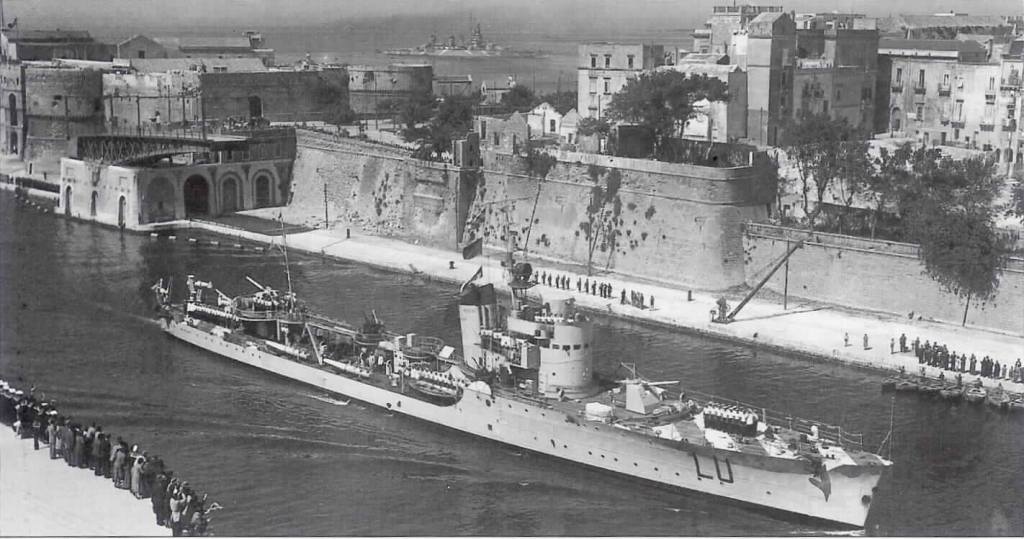

Just after midnight, Force D of three light cruisers and four destroyers engaged 23 ships just north of Crete. They were expecting Italian battleships, heavy cruisers, destroyers, and assault landings ships. What they found were 22 Greek caiques, the ubiquitous Aegean fishing trawlers, escorted by a single Italian destroyer. The convoy was packed with two battalions of German mountain troops, six light tanks, some heavy engineering equipment, and ammunition.

13 caiques were sunk, but the rest were saved by one of the unsung heroic naval stories of the war when the escort, the Italian destroyer Lupo, attacked the British force. She didn’t do any damage, but did cause a friendly fire incident and her action (she survived) allowed the rest to escape. One caique actually made it Crete, and landed her troops at Kastelli Kissamos, about ten kms west of Maleme.

Freyberg’s much feared invasion consisted of just 110 German soldiers and three sailors.

The Battle of Crete: The Landings

The reports that arrived at General Student’s 11th Air Corps HQ in Greece on the first night of the invasion of Crete painted a grim picture: Most battalions were at 60% casualties and two failed report at all (they were both effectively destroyed). One battalion vicinity of the Tavroniti bridge on the west side of the Maleme airfield had just 57 effectives. The 7th Fallschirmjaeger Division commander was missing (his glider crashed into the sea). The senior surviving officer in the division was a major. Most battalion commanders were now captains (and in one case a lieutenant), and one battalion commander was the former medical officer. None of the first day’s objectives were taken. The Cretan population was not friendly despite what the intelligence officers briefed. Ammunition was low, medical supplies nonexistent, and there was “a most distressing” lack of water. Commanders all reported that they were just waiting for the inevitable counterattack to sweep them from the island. The attack was doomed, and everyone wanted to cut losses.

Everyone, except Generalleutnant Kurt Student. As Germany’s, if not the world’s, foremost advocate for airborne warfare, he did not want the first divisional airborne assault in history labeled a failure. Against the recommendations of his staff, the requests of his subordinates, the advice of his peers, and even the orders of his superiors (General List told him to begin planning an evacuation), Student decided to continue attacking for one more day. If by dusk on the 21st he could not land a Ju-52 safely on an airfield, he would evacuate the island with the small flotilla of Greek and Italian merchant ships at his disposal.

The dawn capture of Hill 107 and the Maleme airfield electrified Student’s HQ. The fighting around Pirgos and the east end of the airfield was fierce (Andrew’s Bde Cdr sent up a Maori company from the 28th BN that night. They only made it to the town) but Student hoped at least the western runway was clear of direct fire. There was only one way to find out. He summoned a captain on his staff, one of the best young pilots in the Luftwaffe, and told him to fly to Crete, land, and personally report back. If he received any effective direct fire, the air landing of the 5th Mountain Division would be called off, and the 7th FJ evacuated.

The young pilot did so. Although the strip was mess, and he received scattered fire on the approach and artillery fire as he landed, there was no rifle or machine gun fire affecting the west end of Maleme airfield. The intrepid captain loaded some wounded and took back off. Student decided to continue the fight. Because of transport losses, he had a single battalion that was left behind from the day before and ordered them to drop on the airfield to secure it.

There was no Allied counterattack that day. By the afternoon, the Germans established a perimeter. At 1702, the first Ju-52 from Greece carrying 5th Mountain Division touched down on the west runway of Maleme airfield.

Despite heavy damage to the transports, twelve more fresh heavily armed men would arrive on the airfield every six and a half minutes, as long as there was daylight.

The Battle of Crete: The Fall of Hill 107

Due to various leadership, staff, and equipment problems, communications on the island of Crete were abysmal. The Germans actually achieved tactical surprise twice in the initial invasion of Crete: once when Freyberg didn’t tell anyone about the new invasion d-day and h-hour, and a second time later that afternoon when the second wave of Fallschirmjaeger landed around Rethymnon and Heraklion, whose garrisons no one thought to inform of the fighting around Maleme and Chania. Nonetheless, both landings in the East were contained due to unexpected steadfastness from Greek gendarmes and recruits, solid Australian blocking positions and massed counterattacks, a complete civilian “mobilization” led by “Pendlebury’s Thugs”, and quick decision making by Brigadier Chappell, the commander of the 14th Inf Brigade at Heraklion whom Freyberg reinforced because he thought him incompetent. But those troops in Heraklion were desperately needed around Maleme and Canea. Freyberg’s disposition and orders changes to face a still as yet unmaterialized seaborne invasion was deeply affected by bad communications at all levels so most units just executed Freyberg’s last orders and intent. This left nine (!) Allied battalions unengaged on the critical first day and the ones that were nearly overwhelmed.

This was certainly the case for LieutCol Andrew’s 22 New Zealand Battalion holding Maleme airfield, its key terrain of Hill 107, and the town of Pirgos. Freyberg’s changes left the north end of the Tavroniti’s dry riverbed uncovered and this provided the Germans a perfect assembly area to consolidate after the disorganized landings. By 1000 on the 20th, all of his companies were heavily engaged by strong German attacks: C Coy on the airfield, D Coy on the front slope of Hill 107, A Coy and HQ on the back slope, and B Coy in Pirgos. But they held all day. He received unexpected assistance from the Cretan hamlets around the hill (led by their priest), and although the companies took considerable casualties they were holding their own. The problem was Andrew and his company commanders didn’t know they doing as well as they were. Andrew’s increasingly desperate calls for help to Bde HQ went unanswered. His one radio was spotty, land lines were cut, signal flares unseen, and he had to stop sending runners because they never returned. Furthermore he was trapped on the back side of the Hill in his command post out of contact with three of his companies, all of whom he assumed were overrun.

Each company, and some platoons, were fighting isolated actions uncoordinated with the rest of the battalion. On the airfield, C coy had the worst of it, they were the most exposed to Luftwaffe attacks, and faced the most organized attacks due to the riverbed. The commander took it upon himself to launch the bn reserve: two Matilda tanks and one of his infantry platoons. (One tank broke down, and one was stuck on a rock “like a turtle” in the riverbed and abandoned.) The situation was no different for D and A coys.

That night, after 18 hours of hand to hand combat, three of the four isolated commanders, Andrew on the back slope, C Coy on the airfield, and D Coy on the front slope, all came to the same conclusion: they had to withdraw before the Luftwaffe returned in the morning. They were low on ammunition, and each believed they were all that was left of the battalion, with no prospects of reinforcement.

So they all withdrew east to either B Coy in Pirgos or to the 21st Bn.

As the sun rose on 21 May, 1941, the Luftwaffe bombed empty trenches and surprised Fallschirmjaeger occupied an abandoned Hill 107. Maleme airfield, the key to resupply and reinforcement for the FJ, was in German hands. The slaughter and the successes on the rest of the island no longer mattered.

The Invasion of Crete

The Daily Hate by the Luftwaffe arrived with Teutonic precision at 0730, just as it did everyday for the last two weeks. The men of the 22nd New Zealand Battalion and the left behind RAF ground personnel defending Hill 107 and Maleme airfield smoked in their slit trenches, and when the Germans departed, trudged over to their company messes whose cooks prepared breakfast during the bombardment. But at 0800, as most were standing in line for their bully beef and olive stew, orange slices, and biscuits, a larger, heavier sound echoed from the north. Men scrambled back to their trenches as an impossible number of large twin engine bombers, Stuka dive bombers, and Messerschmitt fighters screaming in at treetop level concentrated on the Royal Marine anti aircraft battery on the airfield. Following closely behind this second attack, which had never happened before, came the rhythmic heavy beating on triple engine JU-52 troop transports. They were accompanied by the “tearing whoosh” of wooden gliders crashing on the headquarters company outside of the coastal town of Pirgos, and in the dry Tavronitis river bed on the west end of the airfield.

20 kilometers away, in a quarry on the Akrotiri peninsula, Lieutenant General Freyberg looked up at the the sound of the lumbering transports, commented, “right on time”, and went back to eating his breakfast. His surprised staff had no idea their commander knew the exact time of the attack, but they sat silently like their beloved commander and quietly ate. Freyberg’s very British tendencies of indifference and aplomb in the face of danger served well during the retreat in Greece, but seemed strangely out of place at the beginning of an airborne attack when audacity, initiative, and decisive action in the first 24 hours usually decided the battle. It was even more so when the distinctive crash of a glider was heard less than a quarter of a mile away.

Nonetheless, the first day was an unmitigated disaster for the Germans, the Allied junior officers and NCOs didn’t share their superiors’ lethargy and they slaughtered Germans wholesale. But it didn’t matter. Most of the troops were stuck in defensive positions facing the sea for the expected amphibious assault. Consequently, for every helpless, disorganized, and most likely unarmed German paratrooper killed on that first morning by a Cretan butcher knife, Greek bayonet, Kiwi rifle, Aussie machine gun, or British tank, there were three more organizing in obvious and neglected assembly areas like the Tavroniti river bed. In a few days, there were over 100,000 troops engaged in the battle, but the next chapter in the story of Crete is defined by a single battalion at the far west of the island: the 752 hungry men, mostly from Wellington, of the 22nd New Zealand Infantry Battalion, defending the Maleme airfield and led by Lieutenant Colonel Leslie Andrew, a Victoria Cross recipient from a war twenty years before.

The Chase Is On

On the afternoon of 20 May, 1941, the Swedish seaplane cruiser Gotland spotted the German warships Bismark and Prinz Eugen in the Kattegat between Denmark and Sweden. This information was passed on to the British naval attaché in Stockhlom, who then passed it to the British Admiralty.

The Admiralty was not oblivious to Raeder’s plan to unite the the German surface fleet in the Atlantic. In fact it was thier worst case scenario verbatim. With Bismarck’s sighting, requests went immediately to bomber command to sink or disable the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in Brest, and track the Bismarck. the next day, plans were put into action to recall every available warship in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

The Battle of Crete: The SOE and Cretan Andartes

For thousands of years, the three rich but disparate ecologies of the strategically placed Aegean island of Crete formed a population consisting of fishermen and city dwellers along the coasts, orchard growers and townsmen of the highlands, and shepherds and bandits from the mountains, usually with foreign occupiers attempting to rule over them all. From the Minoan civilization at the height of the Bronze Age, the historic cycle of conquest, repression, animosity, and revolt between these four groups formed the Cretan character: freedom loving, independent, warlike, loyal, generous, frugal, and unforgiving to a fault.

Prior to the Second World War, the Cretans despised the heavy handed and overbearing policies of the Metaxas regime, and for the sins of not toeing the party line, Metaxas had the unruly inhabitants of the island disarmed. But the vendetta cycle must continue, so the Cretans did what they always did: they either made guns, stole them, smuggled them, or joined the army and borrowed them. The Greek Army’s 5th Cretan Division was a disciplinarian’s nightmare (or paradise, depending on the perspective) but its men forged a reputation for tenacity and belligerence that it would serve it well against the Italians in Albania. The departure of the Cretan Division for Albania in 1940 created a void on Crete that was only partially filled by the British garrison in 1941. The Cretans needed “their” army, and British Special Operations Executive was keen to help them fill the void.

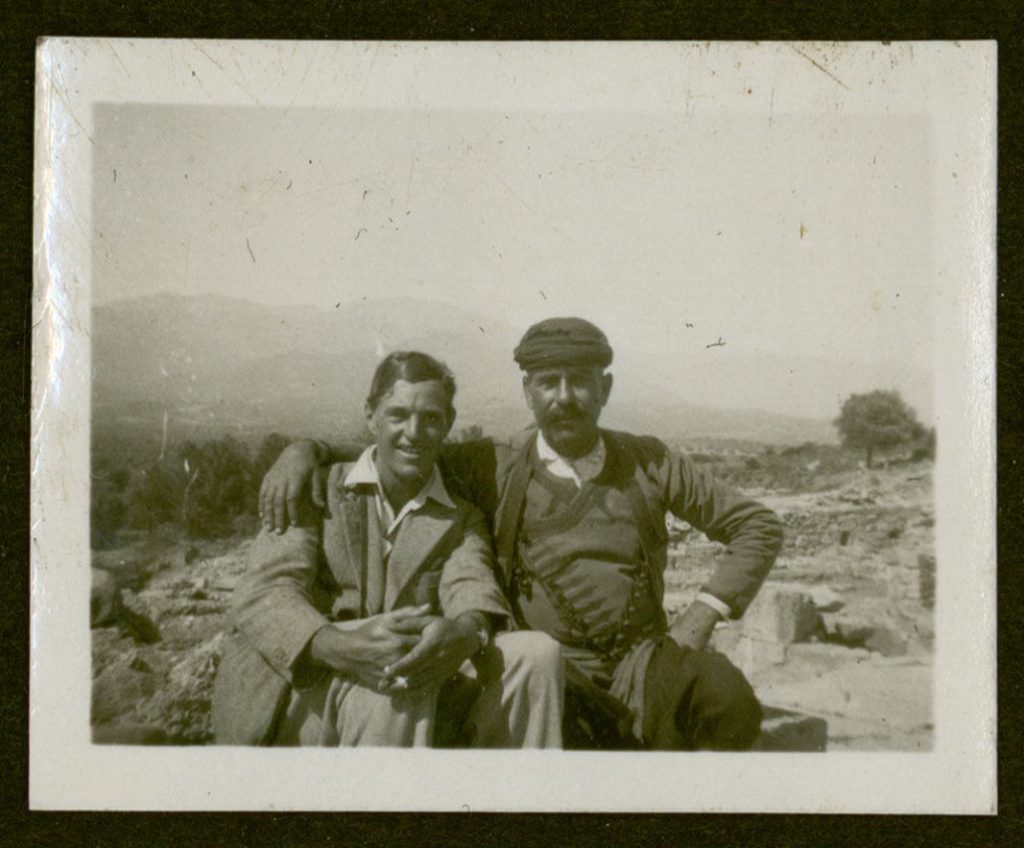

The SOE was a covert British organization tasked with conducting sabotage, espionage and organizing resistance movements across occupied Europe. And nowhere was there a more eclectic group of operatives than in the Aegean, where the SOE recruits tended to be university dons, classicists, “businessmen”, archaeologists, and professors, united in their knowledge of the Greek language. The Aegean was an adventurer’s fantasyland and the exploits of the SOE operatives there read like James Bond novels. (Needless to say where Ian Fleming served…) On Crete, they formed their own clandestine pirate navy and set about organizing the civilian population with eventual goal of replacing the Cretan Division.

One of the most famous operatives was the former curator of Knossos, Dr. John Pendlebury. An archaeologist, rugby enthusiast, and international high jumper before the war, Pendlebury knew every inch of the island and returned undercover as the Foreign Ministry’s vice consul. In order to let his friends know he was up in the hills reforming the guerilla bands that fought against the Turks the generation before, Pendlebury would place is glass eye on his desk as a signal to his friends. He had spent years on the island, and he Cretans considered him one of their own. All of the great Cretan guerilla captains for the rest of the war tied back to him.

On 19 May 1941, Pendlebury returned from the mountains where he meeting with the most famous of the Cretan “andartes kapitan”, “Satanas”. Satanas, Greek for “Satan” because the locals believed only the devil could survive so many vendetta dagger and bullet wounds, was just one of many andartes kapitans living in the mountains. Satanas and Pendlebury planned a resistance stronghold in the caves southwest of Heraklion where local legend claimed the titan Rhea birthed Zeus. But Satanas had one problem: he needed more weapons to properly defend it. Pendlebury could provide much assistance to the andartes, but proper military equipment was scarce in the Eastern Mediterranean in the Spring of 1941.

Little did Satanas and Pendlebury know, equipment would drop from the sky, like mana from heaven, the next day.

The East African (Abyssinian) Campaign

Despite tenacious Italian resistance in the spring of 1941, swiftness of action, solid logistical planning, unconventional solutions, and engaged leadership allowed ad hoc and diverse Allied forces to reverse all of the Italian gains from the year before.

In the north, a large conventional invasion of Eritrea took place from the Sudan in November of 1940 led by the “Gazelle Force”, a mobile column used to conduct reconnaissance, raid, and screen the two division invasion force…kind of like an armored cavalry regiment. It took six months of hard fighting, and not a few setbacks, including a defeat or two, through well-fortified Italian positions before the Italians were routed at the Battle of Keren in late March. (Brig William Slim was wounded by a strafing Italian fighter during this advance).

In the east, Sikhs, Punjabis, Baluchs, and Somali commandos of the 5th Indian Division landed at Berbera in March to recapture British Somaliland. It was the first Allied amphibious assault of the war. Berbera significantly cut down on supply difficulties of supporting from Kenya. After quickly defeating the surprised Italians, they reformed the Somali Camel Corps, and moved inland to meet the Africans moving up from Italian Somaliland.

In the south from his base in Kenya, Lieut Gen Cunningham, (Adm Cunningham’s little brother, funny “Howe” the Brits do that… I fukin kill me) split his command and invaded both Italian Somaliland and southern Ethiopia. Somaliland was seized thru a surprise joint and combined amphibious and land invasion into the teeth of an Italian defense that was expecting them. In the space of five months, the 11th (East) African Division, and the 12th (West) African Div, consisting of units from 14 different nations, arrived, organized, resourced, trained, planned, prepared, rehearsed, staged, and then coordinated a two prong attack into Italian Somaliland. (What can we do in five months?) They seized Mogadishu on 1 March and turned north into Ethiopia.

Cunningham’s other attack was a logistical nightmare across the barren and dry Chelbi Desert by the South African and Rhodesians, in coordination with the separate 8000 man Belgian “Force Publique” from the Congo. This attack went from the trackless desert of Chelbi to the jungles of the Ethiopian highlands at the height of the monsoon. Cunningham hoped to instigate an uprising, but southwest Ethiopia consisted of Ras (kingdoms) that were loyal to the Italians. This attack ended up fighting a brutal counterinsurgency as they moved toward Addis Ababa.

In the fight for Addis Ababa, the successes of Major Orde Wingate’s “Gideon Force” caused Ethiopian “Patriot” units to materialize all across the central, western, and northern parts of the country. The Italians, tied to their bases in the midst of a hostile population, had great difficulty massing on the Patriot units, and when they did, they were ambushed by the Gideon Force. The Italian commander of East Africa, the Duke of Aosta, feared the slaughter of Italian civilians in the capital, and retreated from the city in April.

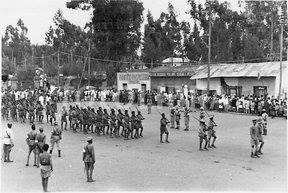

On 5 May 1941, Emperor Haile Selassie, the Ras Tafari and Lion of Judah, made a triumphant entry into Addis Ababa exactly five years after he was forced into exile by the Italians. He was escorted by his Patriots, and Orde Wingate and the Gideon Force. The Duke of Aosta retreated to Amba Algi but was encircled by Lieut Gen Platt (and Slim) from the north, and Cunningham from the south and east. Aosta would surrender 18 May.

Isolated Italian units would resist for another five months and a vicious insurgency would go on for years, but with the Italian defeat, five divisions of troops became available for operations elsewhere: Rommel was pushing on Egypt, the Australians were hard pressed holding Tobruk, Iraq was declaring war, Persia was leaning towards Germany, and the Japanese were threatening to occupy French Indochina, which threatened Burma, Malaya, Singapore, and India. The victory in Ethiopia was none too soon.

The successful East African campaign was the first victorious Allied land campaign of the war. The first Allied amphibious invasion of the war. And the first Axis territory liberated by the Allies in the war.

The Battle of Alcatraz

After a failed escape attempt to seize the notorious island prison’s boat launch, rioting prisoners took hostages and fortified themselves in one of the cell blocks. On 3 May 1946, prison authorities summoned assistance from nearby Treasure Island Naval Station and the US Army post at The Presidio. Two platoons of marines and coast guardsmen led by Gen Joe Stillwell and BG Frank Merrill arrived the next morning. Using tactics they learned fighting dug in Japanese; the marines and the prison guards isolated the prisoners from the hostages and then stormed the cell block. Three prisoners and two guards were killed, with about a dozen wounded. Two captured prisoners were eventually executed in the gas chamber.

U-110 is Captured

By May 1941, Great Britain was slowly being strangled and was down to less than six months of the food and essential supplies required to continue the war. In his memoirs, Winston Churchill would say that the only thing that really scared him during the Second World War was the U-boat threat.

On the morning of 9 May 1941, the German submarine U-110 was part of a Wolfpack that attacked a convoy south of Iceland. One of the escorts, HMS Bulldog, depth charged U-110 and severely damaged it. On the second pass, the Bulldog dropped more depth charges below the U-boat and forced it to the surface.

The German crew abandoned the sub, thinking it was going to sink. But it didn’t. The crew tried to re-board but some machine gun fire from a quick thinking sailor on the Bulldog convinced most of them of the folly of that action. None the less, the U-boat captain died trying: he assumed there was no need so he didn’t destroy the cipher books, message logbooks, or the Enigma machine, used to decode messages from fleet headquarters, before abandoning ship. A boarding party from the Bulldog recovered it all.

The capture of U-110 was an intelligence bonanza for Dr Alan Turing and the British code breakers at Bletchley Park. The Allies were already reading the Luftwaffe’s mail, within the month they were also reading the Kriegsmarine’s. The combination of the two allowed the British to reroute convoys away from German reconnaissance planes, surface raiders, and U-boats, not to mention target Rommel’s supply convoys between Italy and Libya. Merchant marine losses dropped significantly. It was the turning point in the Battle of the Atlantic that year.

The Battle for Crete: Perfect Intelligence and Imperfect Understanding

On 12 May 1941, Group Captain Beamish walked into LieutGen Freyberg’s “office” in the quarry on the neck of Crete’s Akrotiri peninsula, ostensibly to get his ass chewed for the Luftwaffe’s “Daily Hate”, and the RAF’s lack of response, but actually to give the commander his brief on the latest Ultra intercept. Of the 35,000 Allied troops on the island, only Beamish and Freyberg knew of the source, and even existence, of the “Most Reliable Sources” or “Orange Leonard” communiques.

OL-2168, dated 12 May 41 was the analysis of a Luftwaffe order delaying the invasion of Crete from 17 May to 20 May due to the need for an Italian tanker filled with aviation fuel to make its way down the Adriatic. The Luftwaffe order also detailed a change in the invasion’s task organization: the initial landing would still be made by the 7th Fallschirmjaeger Division, but the follow on troops would not be made by the 22nd Air Landing Division, which would stay in Romania, but by the 5th Mountain Division, which was badly mauled in the Greek campaign but reorganized and reinforced for Crete. After the parachutists seized an airfield, the 5th Mountain would be air bridged to Crete from Greece just as the Luftwaffe gad done for Franco’s army from Morocco to Spain five years before.

But the Bletchley Park analyst that composed OL-2168 either misread the order, or more likely, presented the worst case scenario to cover his ass. OL-2168 stated that the invasion of Crete would be made by not two, but three divisions, the 7th FJ, 22nd AL, and 5th Mtn with airborne and air landing components, and a supporting sea borne landing. Freyberg assumed the 5th Mtn was going to make an amphibious assault, as opposed to a landing on a stretch of beach already secured by the parachutists. Despite all of the other evidence to the contrary: a Luftwaffe commander, airfield objectives, lack of German or Italian landing craft, British naval dominance around Crete at night etc. (including future OL comms that clarified the situation) Freyberg was convinced the amphibious invasion was the main effort and altered his orders and disposition accordingly. Nearly half his troops, and almost all of his artillery, now guarded beaches against a non-existent threat.

Churchill’s “fine opportunity for killing parachutists” was slowly turning into a fine opportunity for killing and capturing British, Commonwealth, and Greek troops.

You must be logged in to post a comment.