Tagged: WWII

The Siege of Leningrad

On 8 September 1941, Hitler’s Army Group North reached the southern shore of Lake Ladoga outside of Leningrad, the symbolic home of the Bolshevik Revolution, and one of the Germans’ three objectives for Operation Barbarossa. It effectively cut the city of 2.5 million off from the rest of the Soviet Union. Two days later, the German High Command requested that Finnish troops seize the city through the weakly defended northern approaches. However, Finland was at best a reluctant German ally and Marshal Mannerheim, the CinC of the Finnish Army, refused stating that Finland’s war aims only allowed for the recovery of territory lost in the Winter War with the Soviet Union in 1940. It proved to the last chance that Germany had to seize the city in the war.

Operation Typhoon, the campaign to seize Moscow, was scheduled to launch in October and the tired 4th Panzer Group, which fought its way to Leningrad, was needed. The Siege would be carried out by the foot sore remainder of Army Group North which had an extremely difficult time keeping up with the Panzers. Nevertheless, the Germans thought the city would starve in a matter of weeks.

The only route into and out of the city was over Lake Ladoga, which was under constant artillery bombardment and Luftwaffe attack. The journey over the Lake, in slow boats in the summer and over the ice road known as the Road of Life in the winter, was perilous. 500,000 non-essential personnel were evacuated in the coming months but not before rats, cats, and dogs were a feast, horse a delicacy and cannibalism appeared in the less affluent neighborhoods. Only draconian measures kept the city from surrendering.

On 16 September, Marshal Zhukov was given command of the garrison and he directed the Soviet commissars that workers and soldiers would receive 500 grams of daily bread ration, officer workers and non-laborers would receive 200, and children and old people would receive none pending evacuation. Failure to comply was punishable by death. One Soviet teenager said later, “I watched my father and mother die – I knew perfectly well they were starving. But I wanted their bread more than I wanted them to stay alive. And they knew that about me too. That’s what I remember about the blockade: that feeling that you wanted your parents to die because you wanted their bread.”

On 17 Sep, the 4th Panzer Group began loading tanks on rail cars for the journey south, effectively beginning the siege.

It would last for 900 more days and claim the lives of 1.5 million.

Private Richard Winters

On 25 August 1941, Richard “Dick” Winters, a June graduate and Magna Cum Laude of Franklin and Marshall College, walked into a recruiting office in Lancaster, PA. With the recent passage of the Selective Service Extension, he figured it was only a matter of time before he was drafted. He’d go to Camp Croft, SC for Basic Training, and then Ft Benning, GA for Officer Candidate School. In August 1942, he volunteered for the new Parachute Infantry, and was assigned to E Company, 2nd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment at Camp Toccoa, GA.

You can watch the rest on Band of Brothers.

Operation Countenance: The Invasion of Iran

The phrase, “The Great Game” usually describes the Anglo-Russian rivalry that played out across Central Asia, especially Afghanistan, in the 19th century, but has its roots in an earlier (and eventually overshadowed) rivalry between the two Great Powers in Persia, modern Iran. For hundreds of years, the Iranian people and shahs were used for both good and ill in the diplomatic, economic, and military maneuvering of the British and Russian Empires. In the late 19th century, Iran began asserting its own political independence by establishing ties to the new German Empire. In 1925, a new Shah came to power, Reza Shah Pahlavi, and began a massive modernization program funded by the nationalization of the Anglo-Iran Oil Company (Today we know them as BP), and much foreign assistance, particularly German and Italian.

Reza Shah declared neutrality at the outset of the Second World War, but both Great Britain and the Soviet Union suspected that German advisors in the economy and to the Shah had outsized influence over Iranian foreign policy. After the German Invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Stalin was desperate for Lend Lease supplies and FDR was more than willing to provide them, but the convoy routes through the Arctic Circle were especially dangerous. The old Anglo-Russian trade routes through Iran, especially the railroad from the Persian Gulf to the Caspian Sea known as the “Persian Corridor”, were a perfect compliment.

By the summer of 1941, the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Arabian Sea, and northern Indian Ocean were no longer considered war zones, and could be freely transited by American ships. The British had just secured Ethiopia, Somaliland, and Eritrea from the Italians, cleared Iraq of Fascists, and threw out the Vichy French from Syria, which released several Indian divisions for duty elsewhere. The Soviets additionally wanted an excuse to seize Iran as the next Socialist republic, and secure the oil fields around the Caspian Sea. Britain also saw a pro German Iran as a destabilizing influence to eastern India, and neutral Turkey. When British diplomats delivered an ultimatum to the Shah on 17 August 1941 to expel all Germans from Iran, it didn’t matter what he said: Iran was going to be invaded.

On 24 August, British and Indian troops crossed into Iran from Diyala and Basra in Iraq, in a surprise attack which quickly defeated the Iranian Army that Shah Reza spent a decade and half modernizing with great difficulty. And his new roads expedited the invaders movement in the country. The next day, three Soviet armies did the same from the Transcaucasus and Turkmenistan. In just four days, Soviet and British troops met at Qazvin, just north east of Tehran, and the Shah sued for peace.

The first Americans to facilitate the Persian Corridor arrived a few days later (In 1941, British and Soviet troops were needed for fighting. By 1943, 30,000 Americans were serving in Iran maintaining the Persian Corridor). The first convoys and train loads of American supplies to the Soviet Union would commence in just a week. 30% of all Lend Lease supplies to the Soviet Union would transit through Iran.

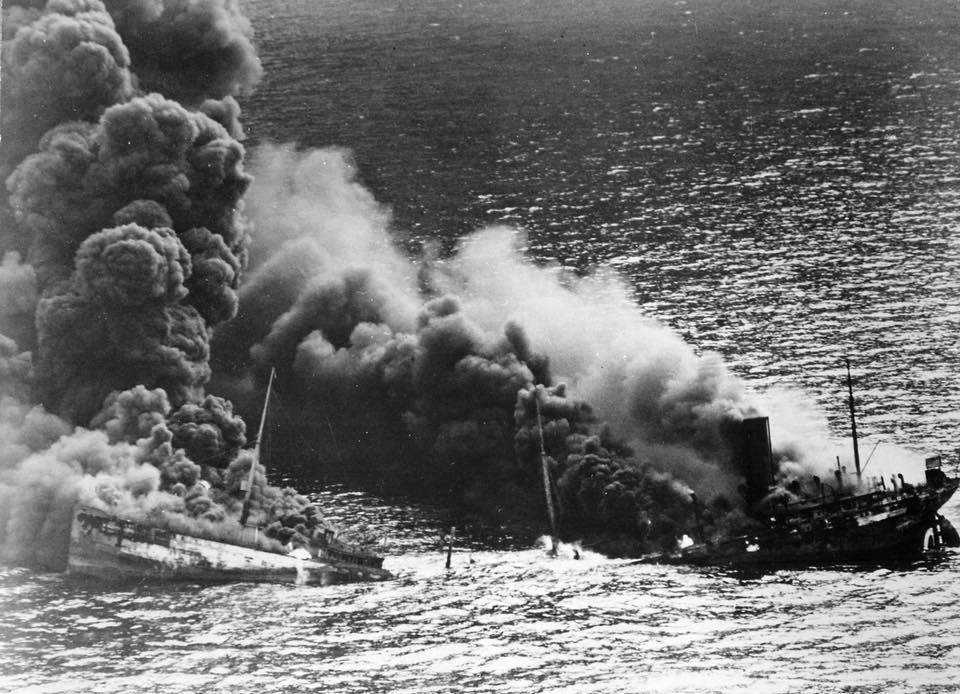

U-38 Sinks the Longtaker

After Denmark surrendered to Germany in 1940, Great Britain invaded Iceland, a Danish protectorate, to prevent its use by Germany in the Battle of the Atlantic. When The US approved the Lend-Lease Act, one of the leased bases was Iceland and the US 6th Marines garrisoned the island (which freed the British garrison to fight).

On 17 Aug 1941, the unescorted Longtaker, a Panamanian flagged steam merchant was enroute to Reykjavik to resupply the garrison with food and timber. Panama, though also technically neutral, was an American protectorate due to the Canal Exclusion Zone in all but name. The Longtaker was spotted by U-38, and sunk with torpedoes. The Longtaker sank in under a minute, and six of the 25 crewmen survived, but three more would die before they were picked up by a US destroyer 20 days later.

The Longtaker Incident was the first US ship sunk in the Atlantic, and the first of a series of encounters that directly led to FDR relaxing the US Navy’s ROE. Within a month, a state of undeclared war existed between the US Navy and the German Kriegsmarine around the world, months before Pearl Harbor.

Anders’ Army

The Soviets captured or deported nearly 325,000 Soldiers and civilians after the dual German/Soviet invasion of Poland in Sep 1939 (and murdered another 100,000). But by August 1941, Stalin was desperate for soldiers to repel the German invasion of the Soviet Union. In conjunction with the nascent Polish Govt-in-exile in London, Stalin agreed to establish a “Polish Army of the East”. Stalin signed the order on 13 August 1941, and the Gen Wladyslaw Anders, a former cavalry brigade commander in 1939, was chosen for the army’s commander. The gulags and prisons across Siberia were combed for Poles still healthy enough to train and fight. By the end of 1941, Ander’s had 25,000 soldiers and 1000 officers training deep in Siberia, and were supported by about 60,000 “camp followers” (for lack of a better term).

Anders was the senior surviving Polish officer captured by the Soviets in 1939. On 14 Aug 1941, the day after the order was signed, Anders was released from the NKVD’s dreaded Lubyanka Prison, one of only a handful of human beings in history that ever walked back out of Lubyanka after being sentenced there.

Operation Dervish: the First Arctic Convoy

On 21 August 1941, Operation Dervish was launched from Hvalfjoror, Iceland, when five British and one Dutch merchantmen left the harbor to convoy to Archangelsk, Soviet Union, far above the Arctic Circle. As it was the first such convoy into unknown waters, it was heavily escorted lest a German success against the convoy be seen as the Allies balking in their commitment to help the Soviet Union who was doing the lion’s share of the fighting against Germany. Dervish was escorted by three destroyers, three minesweepers, and three anti-submarine trawlers, with a heavy cruiser and three destroyers on patrol in the Norwegian Sea to deal with German raiders if needed.

The Dervish convoy was unlike any other convoy so far in the war. The bitter cold, icebergs, and unpredictable storms made the ten day journey treacherous. Combatting ice buildup on the ships was a constant chore, and the perils of not doing so were quickly felt when on the third day, ice formed from normal sea spray grew so heavy and thick on one trawler that it nearly capsized. The entire convoy made it safely to Archangelsk on 31 August without German interference. (The Germans had no air reconnaissance in Norway at the time. That changed quickly once word got out.)

The Soviet reception (or lack thereof) at the port threatened to derail the whole operation. No stevedores were available so the sailors unloaded the ships themselves, only to face the wrath of the local Soviet bureaucracy for faults both unintentional and imagined (Such as placing the crated Hurricane fighters in the wrong warehouse). Events came to a head when sailors were arrested and beaten for not having the proper identity papers. But fortunately, a high ranking Soviet official from Moscow arrived and released the battered detainees, before there was further bloodshed.

The successful Dervish convoy proofed the Arctic route, and established common procedures for both the Allies and Soviets. Further Arctic convoys to the Soviet Union were given the “PQ” designation (the tragic PQ-17 being the most famous), and those returning QP. The Dervish ships themselves would be “QP-1”, and PQ-1 would leave Iceland later in September. 25% of all Lend Lease aid to the Soviet Union went via the Arctic convoys.

Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 Extension

At Roosevelt’s request, Congress voted on 12 August 1941, to extend the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 beyond 12 mos. It passed by one vote.

The first draft class of October 1940 threatened to desert and spray painted “OHIO” (Over the Hill In October) across their barracks, but few did. The extension affected about 70,000 draftees by the time of Pearl Harbor. The vast majority of these men would form the NCO corps of the US Army in 1942. The US Army would most likely not have been able to conduct effective offensive operations in 1942 without the extension.

Operation Barbarossa, Fuehrer Directive 33, Supplement 1

The first five weeks of Operation Barbarossa were a smashing success. The Wehrmacht encircled and destroyed hundreds of Soviet divisions, and had taken almost a million prisoners. At the end of June, the last organized Soviet mechanized corps were destroyed at the Battle of Brody in the largest tank battle to date. The Soviet KV-1s and T-34s were a nasty surprise to panzertruppen in the outmatched PzIIIs, Pz38s, and PzIVs, but Soviet self inflicted logistics, command and control issues, the vaunted 88s flak guns, and Luftwaffe induced supply problems evened the odds. By mid-July 1941, both Army Groups North and Center were within striking distance of their final objectives, Leningrad and Moscow.

But all was not going according to plan. For every dozen divisions the Germans destroyed, Stalin put 14 ill trained, ill led divisions back into the line: just enough to slow them down. Supplies and maintenance were becoming an issue: Most German divisions were at 70% strength and the Panzer and motorized divisions at 50%. Army Group Center’s forward supply dumps were 750km from nearest railhead. Army Group South, separated from the other army groups by the Pripyat Marshes faced much more effective delaying tactics on the Ukrainian Steppe by the Soviets under Marshal Budyonny (and his Political Officer Nikita Khrushchev). Furthermore, the bypassed Fifth Army in the Pripyat Marshes threatened AG South’s flank, and many divisions were forced from the advance to contain them.

On 19 July 1941, Hitler issued Directive 33, which was a very vague order to capture Leningrad, Moscow, the industrial area around Kharkov, encircle and destroy the Soviets facing AG South, and clear the Pripyat. The German High Command, particularly General Halder the chief of the OKW, disagreed with Hitler’s focus on the Red Army in the South. It was clear even at this early stage of the campaign that unlike in France, the army was not the center of gravity. He pushed for continued attack to seize Moscow at the expense of Leningrad, the Ukraine, the much needed reorganization and refit of Army Group Center, and the destruction of the Red Army in the South. Unlike Napoleon’s invasion 130 years before, Moscow was much more important to Stalin than to Tsar Alexander. Moscow was the cultural, industrial, administrative, and communications center for the Soviet Union, the Communist Party, and Stalin’s regime. Virtually all rail traffic west of the Urals went through Moscow. On 26 July 1941, there just 19 under strength Soviet divisions between Army Group Center and Moscow. Finally, Halder knew Stalin would defend it with everything he had left, which incidentally would satisfy Hitler’s fetish for destroying the Red Army.

The ill Hitler disagreed. The Soviet armaments and tank factories were in the south and that’s where the most effective resistance by the Red Army was. They had to be crushed. Moreover, the German economy and Wehrmacht were desperate for oil, which could only be obtained in quantity from the Caucuses. On 27 July Hitler issued Supplement 1 to Directive 33, which ordered AG Center to clear the Pripyat marshes. Even worse, Supplement 1 stripped Army Group Center of its two Panzer Groups: the 3rd to the north to isolate Leningrad, and the 2nd south to seize Kharkov. Those troops would not be able to participate in the attack on Moscow until September, at which time they’d be even more in need of a respite. Moscow would have another month to prepare its defenses.

Operation Barbarossa: the Invasion of the Soviet Union

On 22 June 1941, the largest, costliest, and most bitter, brutal and destructive military campaign in recorded history began when four million mostly German troops stepped off along a thousand mile front in their long march to destroy the Red Army.

Most Red Army units were taken completely by surprise. Up until 21 June, Nazi Germany and the Communist Soviet Union were defacto allies. Furthermore, Stalin’s purges had eviscerated the Red Army, and even the limited reforms brought on by Marshal Georgy Zhukov after the near defeat in Finland the year before couldn’t change the fact that the quickest way to get shot or sent to Siberia was showing any capacity for independent thought. The new T-34 and KV-1 tanks, which were far superior to anything the Germans had, were the Soviets’ only tactical advantage, though the lack of any competent supporting leadership or logistics and communications systems rendered them mostly ineffectual.

But what the Soviets lacked tactically was more than compensated for in the long run by the Germans’ flawed strategic thinking. “Blitzkrieg” was an operational concept not a strategy, but Hitler was using it as one. Blitzkrieg finally had its bugs worked out after poor showings (in professional warfighters’ eyes at least) in Poland, France and the Low Countries, but finally came into its own in the Balkans, even if the still mostly foot bound and horse drawn Wehrmacht was not equipped to properly exploit it. In any case, Blitzkrieg was enemy focused, not terrain focused and its ultimate objective was always the destruction of the enemy army. Hitler believed that a quick campaign to destroy the Red Army would cause the “whole rotten house to crumble down”. He could not have been more wrong.

Hitler underestimated Stalin’s control of the population and willingness to sacrifice it to slow the invasion. The German General Staff estimated that the Red Army had 350 divisions. By August the German Army killed or captured more than 2 million Soviet soldiers and identified more than 600 divisions. The stunning advances and destruction of entire Soviet fronts in July and August turned into the realization in September and October that the Red Army didn’t matter. In the vast wilderness of the Russian hinterlands, only the Communist regime in Moscow mattered. But by then it was too late: the weather turned and the Eastern Front had turned into an apocalyptic battle of attrition.

Upon hearing of Barbarossa, Churchill was asked if he would support Stalin despite him standing for everything Churchill opposed. He replied, “If Hitler invaded Hell, I’d at least make a favorable reference to the Devil”.

The first phase of the Second World War was over; it’s most destructive phase had begun.

The Battle of the Atlantic: the U-boats’ Lifelines Are Severed

The capture of a fully functional five rotor Enigma machine off of U-110 in early May, 1941 allowed Bletchley Park to read the German Kriegsmarine operation’s orders within days, and sometimes hours after they were transmitted.

The first use of the newly available intelligence windfall were the locations of all of the German tankers and supply ships that U-boats used to replenish without going back to port. Between 2 and 5 June 1941, four Norwegian and Danish flagged tankers, and two freighters packed with torpedoes and food were sunk. The lost ships so upset the German rotation that the operation was the equivalent of sinking 30 U-boats. The British let slip to a known German double agent that the ships were identified due to the preponderance of search assets in the Atlantic because of the Bismarck, and a spy in the Kriegsmarine Headquarters.

You must be logged in to post a comment.