Tagged: AmericanRevolution

The Battle of Bunker Hill

On 13 June 1775, Rebel spies learned of a British plan to sortie out of Boston and break the American siege. Newly named Continental Brigadier General William Prescott devised a plan to fortify the Charlestown peninsula, the only logical place that the British could land.

On the night 16 June, Prescott, and another newly minted brigadier general, Israel Putnam, along with Colonel John Stark, and Dr. Joseph Warren (who should have had command but fought as a private out of respect for the Continental Congress’ 14 June decision) led 1400 men to fortify Bunker Hill, just past the Charlestown Neck. Whether by design or error, the Patriots fortified Breed’s Hill further down the peninsula, and then did not inform anyone at the Cambridge camp of the change. The decision would have grave consequences on the future battle.

The British were surprised (and would continue to be throughout the war) at the American ability to heavily fortify a position overnight, but it didn’t matter. With the Americans on Breed’s Hill, all the British had to do was land near Bunker Hill to win the battle. If the British occupied Bunker Hill, they would cut off Prescott’s force from the American siege lines, and then all they had to do was wait for them to run out of food and water and the Americans would surrender. British Major general Henry Clinton, actually proposed this course of action but was overruled by his peers. Major general William Howe, the new British commander who had just recently replaced General Gage, wanted nothing to do with an American surrender: He wanted to use the might of the British Empire of the to crush the rebels. He didn’t just want to defeat the Americans, he wanted to send a message about the futility of resistance. Fear was to keep the rebels in line – fear of the British Army and Royal Navy.

On the morning of 17 June 1775, Howe landed 3,000 men on the peninsula while the Royal Navy bombarded the Americans. The British initially didn’t attack, they sat on the beach and drank tea waiting for reinforcements. This gave time for Prescott to notice another flaw in his defense, Breed’s Hill could be outflanked to the north, and the entire Rebel position turned. Fortunately, Howe’s dithering allowed John Stark and New Hampshiremen to quickly scrape out a trench along a rail fence which blocked any movement north of Breed’s Hill. When Howe finally did attack, he sent a feint against Breed’s Hill and his main effort slammed into Stark, and was promptly defeated. Howe’s attack would have been successful had it occurred an hour earlier during morning tea time. In any case, when the British advanced up the hill Israel Putnam gave the famous order, “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes”, a common order in the age of the musket, while John Stark used a more practical series of painted stakes in the ground 100 paces out.

The American’s inflicted heavy casualties on the initial British attack and they retreated back to landing area, much to the jubilation of the defending American militiamen. Howe tried again, this time reversing the attacks, with the main attack on Breed’s Hill and the feint against Stark, but with the same result. The defeated British streamed back to the landing area, leaving their dead and screaming wounded littering the hill. After the second attack, the Battle of Breed’s Hill was a resounding American victory. Had the battle not occurred on the Charlestown peninsula, the names “John Prescott”, “Israel Putnam” and “John Stark” would be household names in America.

The Battle of Bunker Hill occurred on the Charlestown peninsula, and that fact was the reason the British could reform for another attack. Howe refused to allow the boats to transport his defeated troops back to Boston. Stuck on the beach with nowhere to go, Howe and his staff and subordinate general officers rallied the British troops. They reorganized the formations, their staffs filled in for the fallen officer the Americans deliberately targeted, and Howe personally led the third attack.

As the situation stood the Americans couldn’t defeat a third attack. They impotently watched the British reform on the beach. Prescott couldn’t attack due to the untrained nature of his militia, but more importantly the American were running out of ammunition. The main army at Cambridge was continuously feeding troops and supplies onto the Charlestown peninsula, but the situation to the west of Breed’s Hill was chaotic, to say the least. Many American troops and most of the powder and shot stayed on Bunker Hill, and never made it to Prescott. When He departed the night before, Prescott said he was going to defend bunker Hill, so that’s where his supplies and reinforcements stayed. Few American officers marched their men to the sound of the guns, and only went where they were told. Furthermore, Prescott left no one on Bunker Hill to coordinate the reinforcements and desperately needed supplies. Finally, the Royal Navy was shelling the Charlestown Neck and Bunker Hill to isolate Breed’s Hill. Many American militiamen got their first taste of cannon fire there, and wanted no more of it. Hundreds turned around and went home.

The Americans had few casualties so far in the battle and if Prescott had the men, powder, and shot sitting on Bunker Hill, he could have defeated Howe’s third attack. But he didn’t, the Howe’s third assault carried the earthworks at bayonet point. The Americans just couldn’t stand against the British bayonet (…yet). They retreated off the peninsula. The retreat was disorganized, but several units surprised the British with their dogged and orderly fighting withdrawal, especially John Stark’s New Hampshire regiments. Many British officers were impressed with the fighting quality of the Americans when they were obviously properly trained. Nonetheless, most of the American casualties were during the retreat, including both William Prescott and Dr. Warren, whose deaths were a grievous blow to the American cause.

All was not lost though. Howe refused to follow up his victory, and continue the attack into the disorganized and defeated Americans. The newly coined Continental Army was shaken by the losses at Bunker Hill and its defeated defenders streaming back into camp. In any case, it did not have the powder for another battle. The vast majority of the Continental Army’s powder was used up or lost at the Battle for Bunker Hill. Had Howe pushed, the entire Continental Army may have broken up.

Fortunately for the Americans, Howe didn’t, and he settled the Pyrrhic victory at Breed’s and Bunker Hills. Howe had defeated the Americans, but he had so many casualties, Howe would not be able to lift the siege anytime soon. Clinton remarked in his diary, “A few more such victories would have shortly put an end to British dominion in America.” The Battle of Bunker Hill was a propaganda victory for the Americans. The amateur Americans had stood up to the mightiest army in the world and threw it back twice with horrendous casualties. The British recognized that Americans were serious, and capable. The defeat at Bunker Hill had far reaching repercussions on American operations. For the next three years, American planning would be dominated by “Trying to create another Bunker Hill.”

The Continental Army

On 23 April 1775, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress authorized the formation of 26 line infantry regiments in order to organize the impromptu army that formed around Boston to besiege the British after their defeat at the Battle of Concord. Connecticut, New York, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire quickly followed suit.

On 14 June, 1775, the Second Continental Congress authorized the recruiting, training, and equipping of ten companies of riflemen, to serve as light infantry, from Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and New York, with a minimum age of 16, 15 with parental consent. In the tactics of the day, a single light infantry company was part of an infantry regiment made up of ten or so other line infantry companies. The line companies would form the battle line, while the light infantry company would move forward in an open formation, defeat the enemy’s light infantry then disrupt the enemy’s line by sniping their officers and forcing them to prematurely discharge their weapons before the line infantry engaged. Outside of battle the light infantry were the scouts and foragers of the regiment.

By authorizing the light infantry companies which were subsequently attached to various Massachusetts line regiments around Boston, the Second Continental Congress effectively “stealth nationalized” the colonies’ legislatively approved provincial armies. The colonies planned on that eventually, since Massachusetts in particular, wanted help paying for and equipping the army. (The provincial officers hated the new riflemen and complained they were the most I’ll-disciplined, rambunctious, and troublesome men in their formations. Later, in 1776, the original ten companies were reassigned from their colonial regiments to form the 1st Continental Regiment.) Furthermore, the Second Continental Congress specifically named four major generals and seven brigadier generals. The Congress conspicuously left off George Washington’s name, much to the irritation of his rivals, whom they announced as Lieutenant General and Commander of the Continental Army the next day.

This We’ll Defend.

Happy birthday, United States Army!

The Battle of Waxhaws and Tarleton’s Quarter

In the autumn of 1779, the failed Franco-American invasion of Georgia saw the death of popular American general Casimir Pulaski in the American defeat at the Siege of Savannah. Sensing that they could bring the Southern Colonies back into the fold, the British invaded South Carolina in the spring of 1780. The Continental Army under Benjamin Lincoln withdrew to Charleston to secure America’s most important city in the South. Lincoln’s Southern Army was surprised and defeated at Moncke’s Corner and Lenud’s Ferry which cut Charleston off. On 12 May, 1780, Lincoln surrendered Charleston and 5000 men in arguably America’s worst defeat in the American Revolution. British Commander-in-Chief Sir Henry Clinton then cleared Patriot strongholds in Georgia and South Carolina. By mid-May, Patriot sentiment in the Southern Colonies was at its lowest, and its leaders hid from Loyalists who flocked to the British.

The only organized American force left in South Carolina was the 380 men of the 3rd Virginia Detachment under Lieutenant Colonel Abraham Buford. (He was the great uncle of Brigadier General John Buford of Gettysburg fame.) The 3rd Virginia was a composite force of men from several Virginia regiments with attached artillery. Buford’s 3rd Virginia was the advanced guard of Baron de Kalb’s relief force sent by Washington to break the Siege of Charleston. When Lincoln surrendered, the 3rd Virginia, along with some dragoons who escaped Charleston, withdrew back towards De Kalb. On 29 May, Lt Col Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion caught up to Buford at Waxhaws on the border with North Carolina.

Tarleton’s British Legion was a combined arms provincial regiment consisting of infantry, cavalry, and light artillery formed from Philadelphia and New York loyalists. The 450 strong British Legion was known for their distinctive green uniforms, and the ruthlessness and tenacity with which they fought. The infamous British Legion exemplified the idea that the American Revolution was America’s first civil war. Tarleton had defeated the Americans at Moncke’s Corner and Lenud’s Ferry, and looked to do the same to Buford at Waxhaws.

Buford couldn’t run, so he formed a battle line. Tarleton, unwilling to wait for his infantry and artillery, who were still far to the rear, charged his cavalry at Buford. The Continental’s single volley was insufficient to stop the charge and Buford’s line broke. With no way to escape the horsemen, many of the Americans surrendered, asking for “quarter”, or mercy. Recognizing the inevitable, Buford sent a white flag to Tarleton to formally surrender his force. However, before it could arrive Tarleton’s horse was shot out from under him. Tarleton’s men saw their commander go down, and became enraged. They refused Buford’s surrender and massacred any Patriots still on the field, including the prisoners. Though Tarleton was trapped beneath his horse and couldn’t restrain his men, it probably wouldn’t have mattered. The British Legion was notorious for their brutality, and Tarleton was already reprimanded for their conduct at Moncke’s Corner. As commander, Tarlton was responsible for his men’s actions, and the British Legion’s failure to protect its prisoners became known as “Tarleton’s Quarter”. Few Patriots would willingly surrender to the British in the South thereafter. One of Lord Cornwallis’ aides wrote that “the virtue of humanity was totally forgot” at Waxhaws.

In a single engagement, Tarleton and the British Legion undid years of British diplomacy, goodwill, and victory in the South. News of the Waxhaws Massacre spread like wildfire and “Tarleton’s Quarter” became its rallying cry. Volunteers and fence sitters across the Southern states flocked to the Patriot cause, and most Loyalists stayed home. In less than a month, Patriot militias and partisans sprung up throughout the Carolinas and Georgia. Tarleton’s Quarter directly resulted in the rise of Patriot leaders Thomas Sumter, Francis Marion, Andrew Pickens, and Elijah Clark, among many more, whose partisans made the South untenable for the British. News of the Waxhaws massacre brought east the “Overmountain Men”, Patriot militias west of the Appalachians, who decisively defeated the loyalist militia at King’s Mountain, ending any chance for the British in the Southern colonies.

With an unfriendly countryside in the Carolinas, Lord Cornwallis was forced north into Virginia after attempting to destroy the new Continental Army under Nathanial Greene. Cornwallis sought refuge at Yorktown.

A local of Waxhaws, Scots-Irish widow Elizabeth Jackson, was horrified at the needless bloodshed by the British on 29 May 1780, which happened practically on her doorstep. She encouraged her 16 and 13 year old sons, Robert and Andrew, to join the Patriot militia. Andrew went on to be the 7th President of the United States.

The Capture of Fort Ticonderoga

After the battles of Lexington and Concord, 20,000 American minutemen descended upon Boston and laid siege to it. But the siege quickly fell into an impasse. General Gage couldn’t force his way out, because there were too many Americans. And the Americans couldn’t storm the city, because the guns of the British Navy would break up any assault. The Americans needed cannon and powder to dislodge the British. Furthermore there were rumors that a British army was forming in Canada and the Americans would be caught in the middle if it marched to relieve Boston. The Americans needed time to train, organize and equip their army before the British descended upon them from the north.

Two hundred miles away, the massive Ft Ticonderoga fulfilled both of these needs. It dominated the traditional invasion route from Canada into New England along Lake Champlain and was stocked with cannon and powder. The fort was vital to the defense of the colonies in the French and Indian War, but after Canada was ceded to the British, it no longer had much military value. Its walls fell into disrepair, and in 1775 had a garrison of just forty men.

The Americans actually launched two small, but unconnected expeditions to capture the fort. The first, from the army besieging Boston, was led by the aristocratic, ambitious, and very competent former merchant, then colonial colonel, Benedict Arnold. The second expedition was led by Arnold’s polar opposite: the hard drinking, hard living, and hard fighting frontiersman Ethan Allen and the notorious Green Mountain Boys, his personal militia from The New Hampshire Grants. They had been fighting their own war of independence from New York since 1770 (They eventually won, we call their land Vermont today). They temporarily put aside their differences with their cousins to the south to fight the British. On 9 May, the two expeditions joined forces, and Arnold attempted to take over command of both due to his commission from Massachusetts. But the Green Mountain Boys were going to be led by Ethan Allen, and no fancy pants colonel was just going to try and take over. They refused to fight for anyone else and Benedict Arnold was relegated to second in command: a slight that infuriated the proud Arnold.

The next morning, Allen, with Arnold at his side, launched a joint surprise attack on Fort Ticonderoga. They met almost no resistance and literally caught the garrison commander with his pants down. Allen banged on his door, and yelled, “Come on out, ya rat!” Hundreds of French, Indians, Americans, and British were killed or wounded trying to take and retake Fort Ticonderoga during the last war. In 1775 the “Gibraltar of America” fell before breakfast. As the Green Mountain Boys got drunk on the rum stores and the garrison commander’s personal booze stash, then tore the joint apart, Arnold and his men continued on and seized Crown Point, Fort St Jean, and the ships at anchor up the coast.

On 19 May, a letter from Gage arrived instructing the garrison to prepare for a rebel attack.

Ethan Allen wrote a dispatch to the Massachusetts Congress detailing the success of the expedition. He purposely never mentioned his rival’s name.

Benedict Arnold never forgave him.

The Gunpowder Incident

Patrick Henry’s “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” speech and subsequent authorization of the expansion to the Virginia militia infuriated Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia. Dunmore was loathed by Virginians in the best of times, but his temperament just spurred patriots in Virginia to even greater lengths to stand in defiance to the Crown. Virginia patriots amassed arms, powder, ammunition and cannon quickly and in great quantities to outfit the new minute companies. One such cache of gunpowder was located in Williamsburg, Virginia’s capital.

As Israel Bissel was still racing south to bring the news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord to Philadelphia, Dunmore requested and received a detachment of Royal Marines whom he billeted in his mansion. On the night of 20 April 1775, the Royal Marines snuck into the Williamsburg magazine and removed the gunpowder. On their way back, they were spotted. Dispatch riders sped across the city and into the countryside informing everyone that Dunmore was disarming the militias. The Royal Marines loaded the powder onto barges on the James River. The crowd and assembling minutemen were too late to stop the powder from reaching the fleet, so they followed Royal Marines back to Dunmore’s mansion.

The crowd outside the mansion grew large and unruly. Dunmore resorted to arming his servants and prepared for an assault. Only the intercession Peyton Randolph, the Speaker of the House of Burgesses prevented the crowd and the minutemen from storming the estate. Dunmore met the Williamsburg City Council who demanded the return of the powder since it was paid for with colony funds. Dunmore’s seizure of it was used as another example of Crown interference in colonial business. Dunmore then justified seizing the powder to prevent it from falling into the hands of an imminent slave rebellion, but the patriots saw right through the feeble excuse. Cornered, Dunmore offered to pay £330 to Patrick Henry for the powder. Henry accepted, but only if the check was guaranteed by a plantation owner since he didn’t trust the Crown to actually pay. Dunmore agreed and the crowd dispersed.

But by then the damage was done, minute companies were streaming into Williamsburg from all over Virginia. On 22 April a crowd again assembled at Dunmore’s mansion. Virginians still didn’t know what had happened outside Boston, so patriot leaders dispersed the crowd. However afterwards, Dunmore scolded them. He threatened to declare the colony’s slaves free, arm them himself, and “reduce the City of Williamsburg to ashes.” He said, he “once fought for the Virginians” but “By God, I would let them see that I could fight against them.” He wouldn’t have long to wait.

On 29 April, the news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, and the Siege of Boston had reached Virginia. Patriot leaders wanted to immediately expel the British and royal governor. At Fredericksburg, a thousand Virginia militia had assembled, but Randolph and longtime colonel of the Virginia militia George Washington counseled restraint. However, their prudence did not extend outside Fredericksburg. Henry assembled the militia of Hanover County and marched on Williamsburg. Dunmore forbade anyone from assisting Henry and specifically disallowed cashing the check because Henry “extorted the Crown”. But that wasn’t going to stop Henry. Dunmore fled with his administration and family to the HMS Fowey anchored in the York River. With Dunmore gone and Williamsburg in patriot hands, Patrick Henry departed for Philadelphia to attend the Second Continental Congress.

The Gunpowder Incident prematurely amassed Virginia militia in Williamsburg and the surrounding areas, and prevented Lord Dunmore from properly responding to the news of Lexington and Concord. It took six months for Dunmore to coordinate a response to the American rebels in Virginia, and Dunmore’s men were promptly defeated at the Battle of Great Bridge in December 1775. Because of Patrick Henry’s response to the Gunpowder Incident, no further British military operations occurred in Virginia until 1779. During the critical years from 1775 to 1779, Virginians could focus on supporting the American Revolution elsewhere in the Thirteen Colonies. Dunmore’s £330 deposit was one of the first direct financial contributions to the American Revolution.

The Shot Heard ‘Round the World

Paul Revere and William Dawes were not the only riders warning the countryside of the British raid, about a dozen people lost to history took up the alarm. Even more did so later in the morning, most famously Israel Bissel who rode from Watertown Massachusetts to Philadelphia, 345 miles, in four days, shouting “To arms, to arms, the war has begun”. The American system of outriders warning of an attack (usually French or Indian) had been in existence since at least Queen Anne’s War, 70 years before. The Sons of Liberty just coopted it for use against the British. Though there were other riders, Dawes and Revere were the only ones tasked specifically to reach Concord.

On the night of 18/19 April 1775, the British sent out patrols to stop the American early warning. They were only partially effective, and when one was captured, more took their place. “The regulars are coming”, sounded throughout the countryside. Both Paul Revere and William Dawes avoided the patrols and reached Lexington just after midnight. They warned Sam Adams and John Hancock and every house they passed. They then departed for Concord. Just outside Lexington, they met Dr. Samuel Prescott, a Concord native who was supposed to show them the way. The British patrols were further out than they thought, and shortly after they met, one patrol scattered the three riders. Revere was captured, Dawes was thrown from his horse and walked back to Lexington, but Prescott made it to Concord. Prescott warned the Massachusetts Provincial Council, though adjourned until May many were still in town, of the impending British raid.

In Lexington, Captain John Parker mustered his minute company whom fully a quarter were his relatives, and sent out men to watch the road from Lechmere Point. After taking roll, they retired to Buckman’s Tavern to await word from the scouts. Five hours later at dawn, Maj. John Pitcairn with the advanced guard of Lieut. Col. Smith’s column entered the town. Parker formed his men in plain sight on Lexington Green but did not block the regulars’ passage to Concord. About 100 spectators formed on the side of the green. As Pitcairn turned off the road instead of continuing on, Parker said, “Stand your ground, men. Don’t fire unless fired upon. But if they mean to have a war, let it start here.”

An officer rode up to Parker’s 77 man company and told them to disperse, as 180 regulars behind him fixed bayonets and continued to advance. The detachment was intent on finding Adams and Hancock, and Parker’s militia was in the way. Parker felt that their stand had shown the regulars that the Americans were serious, and wishing no unnecessary bloodshed, told his men to disperse. But during the tense standoff, a shot rang out from an unknown source. The British fired a volley followed by a bayonet charge which routed Parker’s men. Eight Americans were killed, ten wounded, and one British soldier was slightly wounded. Pitcairn’s men quickly searched Lexington and found nothing (Both Adams and Hancock were in Burlington, Massachusetts at the time). Pitcairn then rejoined Smith’s column and the British continued on to Concord.

As the British marched, they heard shots fired warning of their approach and observed the American minutemen watching them from outside of musket range. The American early warning system was so effective that towns 25 miles from Boston knew of the British advance while they were still unloading boats at Lashmere Point. By the time Smith arrived at Concord, all of Massachusetts knew of the British raid, and thousands of minutemen were descending on the obvious British route of march.

At 8 am, Smith’s column arrived at Concord. 400 Americans were formed up on the hill across the Concord River northwest of town but were not actually in the town. So under the watchful eyes of the minutemen across the river, the British searched Concord. They found some old siege cannon which they disabled and some gun carriages which they burned on the green. The carriage fire spread to the meeting house, which the British assisted in extinguishing. Smith also learned from loyalists of vast stores of powder at Barrett’s Farm, the route to which was blocked by the Americans.

Smith decided to move on to the farm fully expecting to rout the rebels just as his men did at Lexington. But as they approached the Old North Bridge, the British noticed the Rebels also advanced towards them. The Americans saw the smoke from the green and meeting house, and thought that the British were setting fire to all of Concord. The Concord minutemen were determined to stop the firing of their town, and the other minute companies joined them. Fire was exchanged. Canalized by the bridge and faced by superior numbers of Americans, Smith couldn’t force his way to Barret’s Farm.

With a growing number of hostile minutemen across the bridge, Smith realized the grave situation his exhausted men were in. They had been up all night and had already marched nearly 20 miles. Safety was still another 20 miles away along an obvious route. Every minute brought more Americans. Smith ordered a retreat back to Boston.

The march back was not going to be as easy as the march to Concord. Thousands of minutemen were streaming in from all over Massachusetts. They lined the road back to Boston (now known as “Battle Road”) shooting at the British from behind trees and stone walls as they passed. Only the aggressive nature of the troops he commanded saved Smith’s column from complete annihilation. The British light infantry and grenadiers that made up the raiding force were the best soldiers in General Gage’s army. Despite exhaustion, they continually sent out flanking patrols and conducted pulse charges to engage the Rebels and break up any concentrations along the route. Still, hundreds were killed and wounded.

At 3 pm, 19 April, 1775, 17 hours after notification of the mission, Smith’s column returned to Lexington where it met a much needed relief column from Boston. However, the British didn’t tarry long and after a brief respite outside of Munro’s Tavern to consolidate, reorganize, and wait for stragglers, they continued on. More than four thousand American minutemen were in the area, and more on the way.

The column arrived back in Boston at dusk, protected by the guns of the Royal Navy. The British marched 41 miles on 19 April and fought a running battle most of the time. It is estimated that some marched over 50 miles along the way trying to engage the Rebels. Within days, 15,000 American militiamen surrounded and laid siege to the British inside Boston, some from as far away as Connecticut and New Hampshire.

America had just picked a fight with the most powerful country on the planet. Though America didn’t know it at the time, “The Shot Heard Round the Word” at dawn on Lexington Green started a new phase in world history. The American Revolution had begun.

Two If By Sea

By 1775, the British Prime Minister, Lord North, had had enough. He and Parliament had made conciliatory gestures to the troublesome North American colonies twice already. The first by repealing the Stamp Act in 1766 and the second by repealing the Townsend Acts in 1770. He was not going to do the same with the Coercive Acts. In January 1775, North ordered General Thomas Gage, the Governor General of Massachusetts and commander of the occupying army in Boston, to arrest the nucleus of the shadow government, the Massachusetts Provincial Council, who controlled most of the colony outside of Boston. The Massachusetts Provincial Council met in the crossroads town of Concord and was instrumental in raising rebel “minuteman companies” of militia (because they said they were ready to fight at a minute’s notice) to oppose the British. In February 1775, Parliament and King George III officially declared the Massachusetts Colony in a State of Rebellion.

In April 1775, Gage correctly believed that the radical patriot group Sons of Liberty were behind most of the overt acts of rebellion. On 14 April, Gage finally received Lord North’s specific instructions. On 15 April 1775, Gage received intelligence that two of the Sons of Liberty’s most important leaders, Sam Adams and John Hancock, were in Lexington, 12 miles away. The Massachusetts’s Provincial Council had just adjourned until May and Adams had orders to go to Philadelphia immediately. Furthermore, loyalist spies also reported there were cannon, gunpowder, and muskets for the minuteman companies located further up the road at Concord. As he had several times before, Gage organized a column of troops to capture Adams and Hancock before they departed, and seize the stores from the rebels. Every regiment he commanded wanted to take part in the raid. Because the march to Concord was over 40 miles there and back, he assembled his best troops, the light and grenadier companies, from the regiments in his army.

At 9 pm on 18 April 1775, the tireless Dr. Joseph Warren, one of the few remaining Sons of Liberty in Boston, informed William Dawes and Paul Revere to be prepared to ride. Both Dawes and Revere were couriers for the Sons of Liberty, and Revere had even warned Lexington and Concord of the impending raid two days before. But a general alarm to raise the minuteman companies was beyond Warren’s sole authority. The Massachusetts’s Provisional Council required the five members of the Committee of Public Safety to unanimously vote to raise the alarm. Warren was the only member in Boston. Three were staying at the Black Horse Tavern in Menotomy, across the river, and the fourth was in Charlestown. Traveling and gathering them up for the vote would take time and possibly cause a later alert, if the British moved while he was away. He decided to stay and personally oversee the placing of the lanterns in the Old North Church

Dr. Warren was waiting for the British to move before sending the initial signal. Revere had actually coordinated the system two days before but it was left to Warren to actually initiate it. If Revere and Dawes saw one lantern in the steeple, the British raiding force was moving via the Boston Neck; if there were two lanterns, they moved by boat across the Charles River estuary. They would then alert the countryside of the British Army’s movements and raise the minute companies; Dawes by the Neck and Revere by rowing to Cambridge first. The two riders were to meet Samuel Prescott, a Concord native, just past Lexington to make the journey to Concord. Neither Revere nor Dawes were familiar with the roads west of Lexington and Prescott was to be their guide.

The massing of boats and barges was a clear sign that the British were going to cross the estuary. It was only a question of when it was going to happen. Warren, Revere and Dawes did not have long to wait. It seemed everyone knew what was about except the British troops that were going to participate in the battle. About 9:30pm Lieut. Col. Francis Smith, the commander of the raid was finally informed of the mission.

At 10 pm, 18 April, 1775, 700 troops under Smith and his executive officer, Major John Pitcairn, loaded barges off of the Boston Commons. Dr. Warren immediately had two lanterns placed in Old North Church, and Revere and Dawes departed for Lexington and Concord, rousing minute companies along the way. Their routes were not always safe, Gage sent out officers on horseback to patrol the roads to prevent just such a warning. The British landed at Lechmere Point at 11pm and began their march on Lexington and Concord.

Paul Revere’s First Ride

On 14 April, 1775, the military governor of Massachusetts, British Army General Thomas Gage received instructions to seize members of the Massachusetts’s Provincial Assembly, disarm minuteman militias, and arrest prominent Sons of Liberty leaders known to be hiding in the countryside outside of Boston. Gage had on several occasions already attempted to seize American militia stores and forcibly disband American militias, but this was the first time he had received specific instructions from London to do so. Originally written in January, the instructions authorized Gage to break up the illegal provincial assembly and arrest its members, even its loyalist members. However, every Massachusetts town had its own militia. Isolated, these were not too much of an issue since he assumed they would never fire on British regulars. Together though, they could form a rebel army that could possibly challenge his command in Boston. To form this army, the rebels would need vast stores of powder, supplies, and cannon. British spies reported that the rebels were amassing exactly that at Concord, about twenty miles west of Boston.

Concord was a crossroads town a day’s ride from the city that connected towns west, northwest, and southwest to Boston. It was a natural meeting place for the rebels to coordinate their activity and stores arms and equipment for future use. Due to the hostility of the American populace in the countryside, Gage didn’t want to have his men overnight outside of Boston. Seizing the stores at Concord was the first step in neutralizing the countryside long enough to seize the members of the provincial council. Concord was twenty miles away, a one day’s forced march and back for good troops, but only just. On the morning of the 15th, Gage relieved the light and grenadier companies of each of his regiments, the best troops he had, of all upcoming duties “til further orders”. This tipped off American spies who immediately sent word to rebel leaders of an impending British advance into the countryside. Concord was the obvious target.

On the night of 15 April, Paul Revere, a silversmith and engraver and a courier for the Son’s of Liberty Committee of Public Safety in Boston set off to warn the American rebels. He stopped first at Lexington where Samuel Adams and John Hancock were hiding in the parsonage to warn them of the impending British attempt to arrest them. Revere then proceeded to Concord where he warned its leaders that the British were coming to seize the rebel stockpile. Revere then turned around and headed home to Boston. On the way back, he stopped at Charlestown. There he coordinated with the local patriots a lantern signaling system in the Old North Church, whose belfry was the tallest in Boston. When the British operation began, one lantern would signal the British were marching across the Neck to Roxbury, two if they were moving by boat to Cambridge or Charlestown.

At Concord, Revere’s message set off a flurry of activity. Since the stores of weapons, equipment, cannon, and powder were scattered in fields, swamps, cellars, barns, attics, and yards of the town, moving the stores would take some time. On the 16th the residents of Concord began a frenzy of digging and uncovering, then dragging and moving the stores to towns further away from Boston.

Give Men Liberty Or Give Me Death

In the late 18th century, Great Britain levied deeply unpopular taxes on its colonies in order to pay for the Seven Years War, or the French and Indian War as it was known in North America. Despite what your teachers told you, the taxes were not mainly for the defense of the thirteen North American colonies. They were also to pay for the subsidies to Prussia, who fought Austria, Russia, Saxony, and France on the continent nearly by itself. The “Golden Cavalry of Saint George”, the nickname for British gold in lieu of soldiers to its allies, was over four times what the British paid for the defense of the Thirteen Colonies. After the Seven Years War, Britain’s debt was nearly three quarters of its gross domestic product. The Thirteen Colonies weren’t the most prosperous in the British Empire (the sugar plantations of the West Indies held that honor), but they were the most resilient and could absorb and weather new taxes, if they chose to do so.

The taxes were unpopular because in the colonial charters the legislatures and governors of the Thirteen Colonies had sole authority to tax their people. If the colonial legislatures wanted to raise a tax, that was no problem, they could be replaced if it was too onerous. And they did levy taxes for defense against the French and Indians along the frontier. But there was no recourse if Parliament levied taxes directly i.e. taxation without representation. It didn’t matter if it was for defense or not. British military protection of its colonies was the price the Crown and the Parliament paid for their loyalty. That Parliament taxed them directly was considered double-dipping and a violation of their charter at best, and a violation of the unwritten social contract of empire and their basic human rights as Englishmen at worst. As the thinking went, if Parliament could disregard one of the main tenets of a colonial charter, where would their tyranny stop? Nowhere, if Ireland was any example. Ireland was a ready made case study of direct British Parliamentary rule, and American colonists had no wish to endure that.

The taxes at the end of the French and Indian War sparked widespread discontent among the colonists, and most were quickly repealed, such as the infamous Stamp Tax which placed a levy on all printed paper. The Stamp Act was especially loathed, as it was not only a tax, but it was also an indirect suppression of free speech, a human right that all Englishmen enjoyed. However their repeal did not include the tea tax because Parliament wanted to prove the point that they could tax the colonies directly at will despite their charters. Parliament figured that Englishmen loved their tea too much, and would endure the tax and subsequent higher price. Parliament would get their tax precedent and the colonists their tea. Parliament was wrong.

The Boston Tea Party in 1773 led directly to further coercive laws by Parliament to bring the “petulant” North American colonists to heel. They included the Quebec Act which extended the province of Quebec south to the Ohio River to keep the colonies from expanding west (which was ignored), and the aptly named Coercive Acts aka the “Intolerable Acts”. There were four Coercive Acts: the first closed the port of Boston to trade, the second forbade meetings and gatherings in Boston, the third forbade the detaining of British soldiers in the colonies for crimes committed, and the fourth called for the quartering of British troops in private homes.

By March 1775, the colonies seethed under these laws and rebellion was all but assured between King George III’s Great Britain and his thirteen colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. This was particularly true in New England whose residents were all but in open war against the Crown.

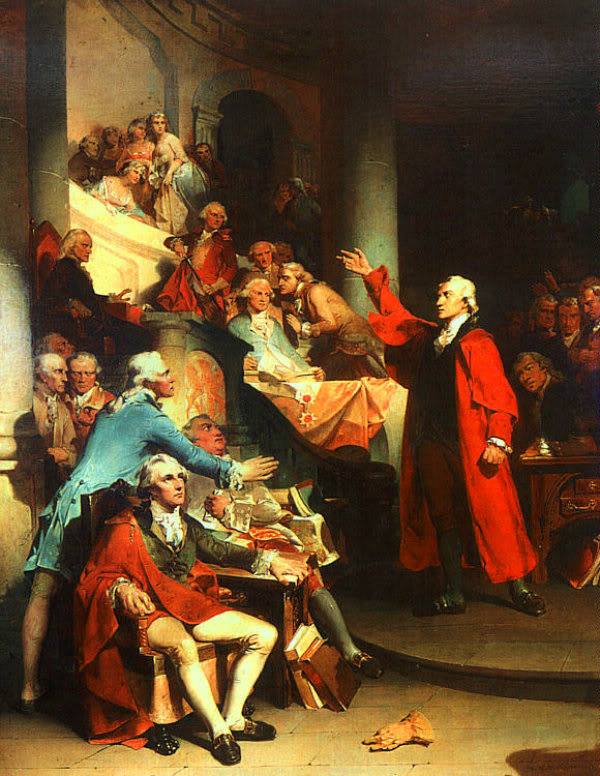

On 23 March 1775, the forcibly disbanded Virginia House of Burgesses defiantly met at St John’s Church in Richmond. During the debate on whether to raise Virginia’s militia to help the patriots in New England, a fiery 40 year old lawyer, Patrick Henry, got up to speak. Patrick Henry was a natural orator who spoke without notes or preparation. As he reached the crescendo of his eight minute discourse in favor of Virginians taking up arms against Great Britain, Patrick Henry concluded,

“It is in vain, sir, to extenuate the matter. Gentlemen may cry, “Peace! Peace!”, but there is no peace. The war is actually begun! The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? What is it that gentlemen wish? What would they have? Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!”

The motion passed easily.

America’s First St. Patrick’s Day

In the 18th century, Ireland chaffed under Great Britain’s rule, specifically Poyning’s Law, the Declaratory Act, and the various anti-Catholic laws imposed and enforced by the state controlled Anglican Church. Poyning’s Law, passed in 1498, denied the Irish the ability to call a parliament unless it was approved by the King of England and his Privy Council. The Declaratory Act, better understood by its official name the Dependency of Ireland on Great Britain Act of 1719, declared that the British House of Lords was the final appellate court for all Irish court cases and that the British Parliament could pass legislation for the Kingdom of Ireland. Finally, through Parliament and the King, the Anglican Church enforced the Penal Laws which were a collection of restrictions and discriminatory laws, such as the Popery Act of 1698, against Roman Catholics. Since Ireland was predominately Roman Catholic, most Irishmen could not hold office, be a lawyer, own firearms or enlist, buy land, vote, intermarry with Protestants, adopt children, convert to Catholicism, buy a horse worth over 5 pounds, and Irish priests were forced to register (1698) in order to preach. Six years later in 1704, Irish priests were outlawed and bounties placed on their heads for their arrest. The register made their arrests quite convenient and lucrative for Protestant bounty hunters.

In 1778, Catholic France allied with the nascent United States of America in her fight against Great Britain. The British feared an invasion of Ireland as French support for dissident minorities on the British Isles, particularly Catholic minorities, was a time honored tradition. The British formed Irish Volunteer companies from Anglican Irishmen to fight any potential French invasion and uprising. However, as more British regiments were sent to the Caribbean and North America, the Irish Volunteers began to take Catholics upon an oath of loyalty. By 1778, the threat of French invasion was minimal, but the Irish Volunteers didn’t disband. With the emerging middle class consciousness caused by the Industrial Revolution, the Irish Volunteer companies morphed into political organizations more concerned with popular local causes, and there was no more popular local cause in Ireland than Irish Catholic emancipation. In 1778, the companies gave an Irish voice to those who advocated for the repeal of the harsh Penal Laws, deemed passé and obsolescent in the Age of Enlightenment. Later that year, the Papists Acts of 1778 mitigated much of the official discrimination against Catholics, but the backlash was severe. By late 1779, Irish Catholics were forced to defend themselves against Anglican riots and violence. The Irish Parliament, called in defiance of Britain, deliberated on how to break the British and Anglican hold on Ireland.

That same winter at Morristown, New Jersey, the Continental Army was enduring “the coldest winter in North America in 400 years”. New York Bay froze solid. General George Washington referred to the winter of 1779/80 as “the hard winter” and worse than the one at Valley Forge two years before. By March, one third of the 12,000 strong Continental Army had deserted, and one third more were not fit for duty. Furthermore, the logistics’ system of the Continental Congress had collapsed upon itself and the states were told to supply their own soldiers at Morristown. Morale was rock bottom.

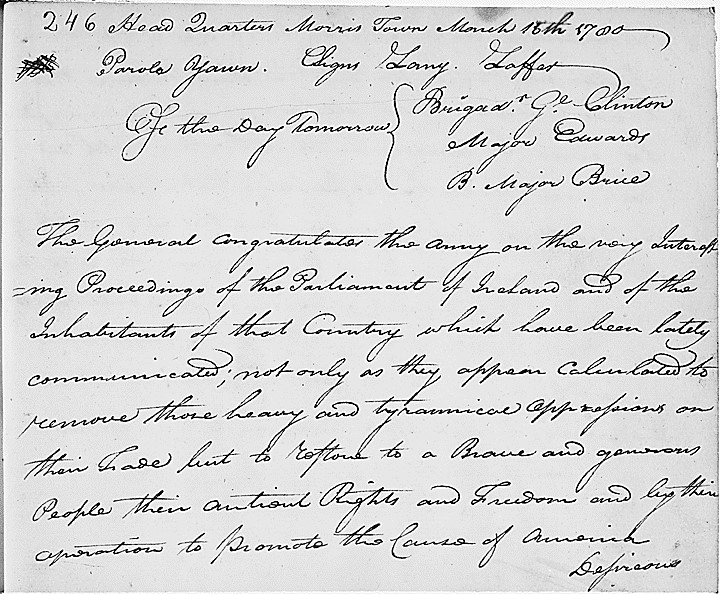

Washington needed to improve morale, prevent a mutiny, give his men some respite to the ceaseless drilling and camp labor, and hopefully prevent more desertions. Irish and Scots-Irish immigrants made up a significant percentage of the Continental Army, about two fifths, with the ratio of officers being larger. Encouraged by his wife Martha who spent most of the winter with her husband, Washington planned something special for his men. On 16 March 1780, Washington a member of Philadelphia’s Friendly Sons of St. Patrick, issued a general order recognizing the Irish quest for freedom from British rule. More practically, Washington gave the Continental Army the next day off to show solidarity with the Irish fight for independence. The next day was the seventeenth of March, St Patrick’s Day.

“Head Quarters Morris Town March 16th, 1780

General Order

The general congratulates the army on the very interesting proceedings of the parliament of Ireland and the inhabitants of that country which have been lately communicated; not only as they appear calculated to remove those heavy and tyrannical oppressions on their trade but to restore to a brave and generous people their ancient rights and freedom and by their operations to promote the cause of America.

Desirous of impressing upon the minds of the army, transactions so important in their nature, the general directs that all fatigue and working parties cease for tomorrow the seventeenth, a day held in particular regard by the people of the nation. At the same time that he orders this, he persuades himself that the celebration of the day will not be attended with the least rioting or disorder, the officers to be at their quarters in camp and the troops of the state line to keep within their own encampment.”

In the Pennsylvania Division, the division commander, Major General Baron Von Steuben, and his two brigade commanders, Brigadier Generals Anthony Wayne and Mordecai Gist, each bought a “hogshead” of rum (63 gallon cask) for their men to celebrate.

Happy Saint Patrick’s Day

You must be logged in to post a comment.