The Battle of Sullivan’s Island

While the British regulars were locked up in Boston throughout late 1775 and early 1776, Americans in the remaining colonies threw out most of the British and loyalist officials. When Howe evacuated Boston, two large expeditionary forces were made available to Howe: one under Gen. John Burgoyne that went to lift the siege of Quebec, and another under Gen. Henry Clinton, which sailed south.

In June 1776, Britain’s only friendly harbor north of the Caribbean was in Nova Scotia. And another was needed to effectively subdue the colonies. With only 4000 men New York and Virginia were out of the question, so Clinton headed south to the supposedly friendlier Carolinas and Georgia.

Clinton sought to link up with Scottish loyalists from the backwoods of North Carolina. However, when he arrived off of Cape Fear, he found out that the Scots were defeated at the Battle of Moore’s Bridge two weeks before so he headed further south to Charleston, South Carolina.

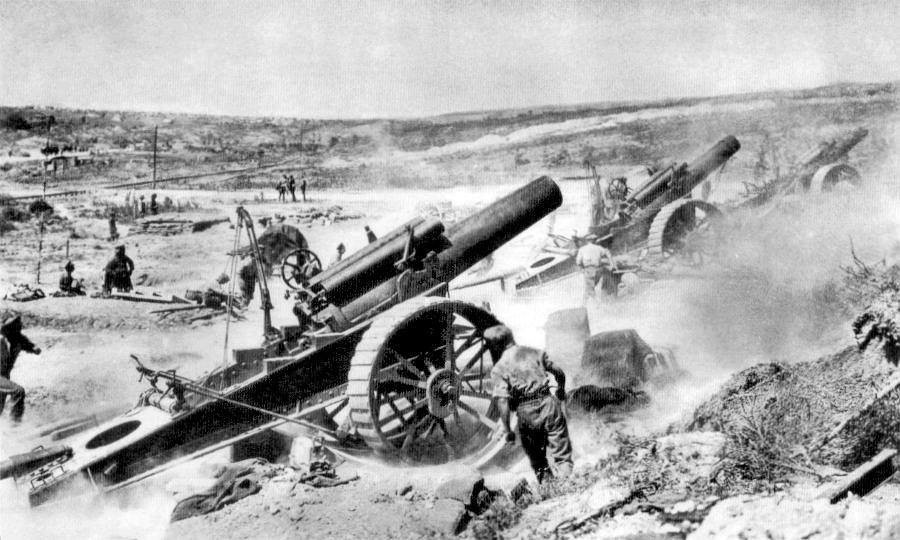

In colonies that were prepared to fight against the Crown, South Carolina was close to the top of the list. Charleston was the third largest city in the colonies, the center of patriot resistance in the south, and home to most of the arms manufacturers in the Southern colonies. Thousands of Scots-Irish patriot militia poured into the city from the backwoods, and fortifications defending the city were started in late March 1776. Unfortunately, they were not completed when Adm Peter Parker’s flotilla of eight warships appeared off the coast in June with Clinton’s men. The northern entrance to Charleston Harbor was guarded by a half finished fort on Sullivan’s Island commanded by COL William Moultrie with 500 men and thirty pieces of artillery. Only two walls of the “fort” we’re started. But they were thick and consisted of palmetto log retaining walls filled in with sand, and had firing platforms for the guns.

On 28 June 1776, Clinton’s men attempted to march on the rear of the fort by fording from nearby Long Island while Parker destroyed the it with cannon fire and landed marines. But the ford was chest deep, and a small blocking force prevented Clinton from ferrying across. Nonetheless, Parker was confident he could complete the task himself.

Parker opened fire and Moultrie responded in kind. To make up for a relative lack of gunpowder, Moultrie’s gunners made every shot count, greatly damaging the fleet. Parker’s fire was continuos and heavy but the spongy palmetto logs absorbed the shot. Most accounts of the battle note the logs of the fort “quivered” when hit instead of splintering. But that didn’t help the men on the platforms whom took a terrible pounding. The high watermark of the fight came just before dusk when the flag Moultrie designed was struck down fell outside the walls. SGT William Jasper yelled “We shall not fight without our flag!” and ran through the fire to grab it. He fastened it to a cannon swab so the city could see it since the flag staff was broken. The act inspired the defenders and they increased the rate of fire, so much so that when dusk fell, Parker decided that any further bombardment would just get his barely floating ships sunk.

Unable to force the narrows, Clinton’s men reboarded. Parker returned to the bigger Long Island to join with Howe’s substantially larger invasion of New York later in July.

You must be logged in to post a comment.