After the defeat at the Battle of Long Island, LTG Washington was desperate for information regarding British operations against Manhattan. On 8 September 1776, CPT Nathan Hale of the 7th Connecticut Regt, a graduate of Yale and a former schoolteacher, volunteered to infiltrate Long Island and ascertain British intentions. He posed as an unemployed schoolmaster, and made his way from Connecticut, to Long Island, and eventually Manhattan, after the British landing at Kip’s Bay.

However, Hale was probably the worst possible choice for a spy: he was tall and “impossibly good looking”. He stood out in crowds. He was earnest, forthright, outspoken, and according to his friends, “incapable of duplicitous action”. Finally, he had a distinctive powder burn on his cheek from a skirmish with the British during the Siege of Boston.

On 20 Sept, Hale collected his notes and sketches of the British Army and Navy in and around New York City, and decided make his escape back to Washington on Harlem Heights. Unfortunately that night, a fire, which started at The Fighting Cocks Tavern, destroyed one third of the mostly abandoned city. The British blamed American spies (and the Americans blamed the British who used the fire as an excuse to loot the rest of the city… but let’s be honest: it was probably the Americans), and the next morning rounded up more than 200 ”suspicious men”, including Hale.

Hale was captured by none other the Major Robert Rogers of the Queen’s Rangers who was unconvinced with the school teacher story of the tall, ruggedly handsome blonde man with a nearly fresh powder burn on his cheek (even though he was actually a schoolteacher). Rogers spun a tale that he was also an American spy and had set the fires. Unfortunately the naive Hale believed him and gave himself away.

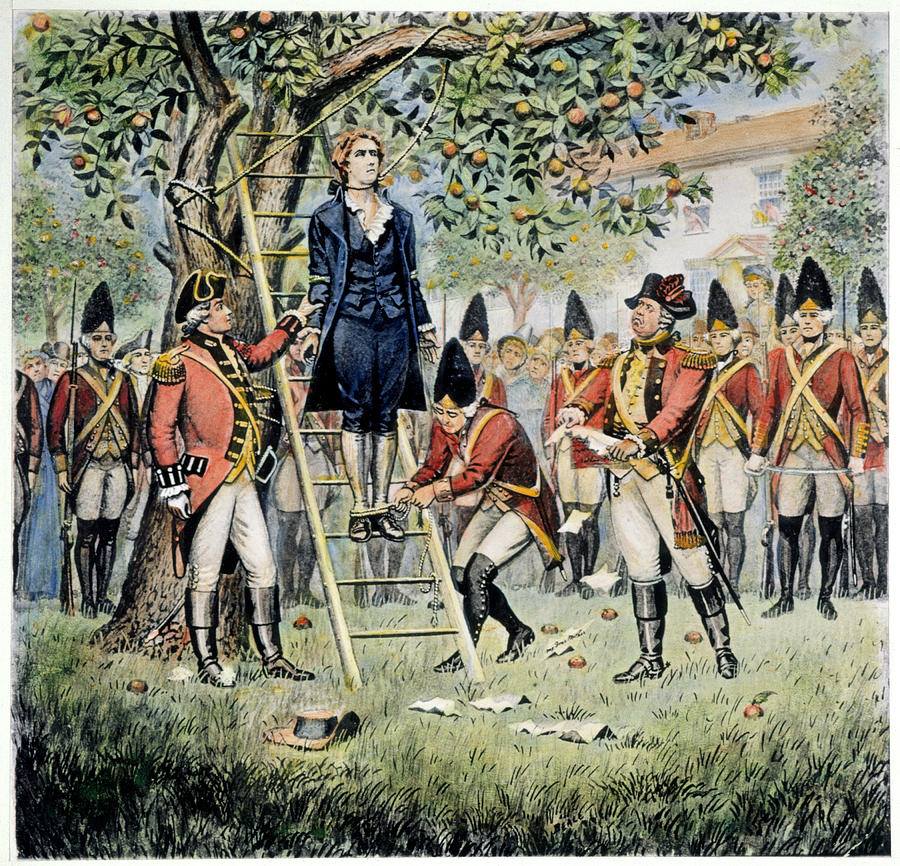

Of the 200 men rounded up as American spies, Hale was the only one who admitted he was a Patriot when he looked Gen Howe in the eye and told him so. According to the customs of war at the time, soldiers not in uniform were illegal combatants and were summarily hanged without a trial. At dawn on 22 September, 1776, CPT Nathan Hale was led to a tree outside of Dove Tavern in New York City, surrounded by only a few British officers and soldiers. But when the hangman asked the 21 year old if he had any last words, Hale, with “great composure and resolution” paraphrased a passage from a popular play at the time and said,

“I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.