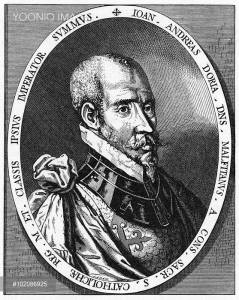

Like the island of Corfu the day before, Don Juan of Austria, the Hapsburg commander of the Holy League’s fleet, splashed ashore on the island of Cephalonia at the mouth of the Gulf of Patras to find it devastated. The Turkish fleet anchored at Lepanto barely fifty miles away scoured the nearby Greek islands for extra galley slaves, provisions, and gunpowder for the upcoming clash with the coalition fleet. He was doing the same, even though he paid his rowers, well if they were Christian, not a convict… and if they lived.

With few exceptions, Don Juan’s 208 galleys would seem familiar to the Turks across the bay, or even the Greek and Roman sailors that plied these waters in the ancient past. Naval warfare in the Mediterranean remained remarkably stagnant for two millennia: oared vessels, whether biremes, triremes, or galleys, packed with soldiers attempting to ram, board and either capture or sink the enemy ships until one side broke. But a recent phenomenon changed that equation: industry produced gunpowder and cannon.

Both the Holy League’s and the Ottoman Empire’s galleys were equipped with cannon, usually one large cannon in the bow, flanked by two or four smaller cannon all pointed forward over the massive ram. But the Ottomans had little indigenous armaments industry and relied mostly on cannon either captured or purchased from arms dealers, whereas Don Juan’s galleys had the largest cannon forged in the latest metallurgical techniques by the finest German and Italian cannonsmiths at the time, that is to say in the world at the time. His guns were heavier, larger, and more numerous. Furthermore, his ships were newer: the Ottomans had been raiding since March, and many were in dire need of repair and maintenance this late in the season. Some of the Holy League’s galleys were so new they had no ornamentation – sixty were created at the Arsenal of Venice over 90 days at the end of spring. (Conventional wisdom says Henry Ford invented the assembly line, the Venetians did the same thing 340 years earlier. To impress a Genoese delegation, the Arsenal once built a galley Ikea-style in 24 hours from the stocks of pre made parts. A record that wouldn’t be broken until America started pumping out Liberty ships every eight hours in 1942. The only difference between Ford and the Arsenal was Ford moved the cars along the line, the Arsenal moved the parts and labor along the line.) But the issue with the Venetian galleys weren’t their number but their manning. They had the largest contingent of vessels, but even with every convict, household guard, citizen volunteer, and condottieri in the city that can pull an oar or man a gun, the Venetians still lacked the weight of mass to close with and engage the packed decks of the Turkish galleys. Don Juan had to augment them with infantry, and the only excess infantry he had were Spanish.

Venice in the east and Spain in the west were natural Mediterranean rivals. Since the expedition’s onset, their contention threatened to unravel the Holy League. Don Juan understood that a coalition of this size would probably not repeat in the near future. But Spain, bankrolling the whole endeavor with gold from the New World, wanted to protect its investment, and instead of fighting for Venetian holdings in the Eastern Med, wanted to wait until the inevitable Turkish attack on Italy the next year. Prior to leaving Messina in September, Don Juan placed thousands of Spanish harquebusiers (soldiers with primitive matchlock firearms) on the Venetian ships. Conflict between the crews and soldiers was inevitable.

Off of Corfu on 4 OCT 1571, a Spanish soldier stepped on a Venetian crewman’s toe, which set off a pitched battle on deck that resulted in the Spanish capture of the galley, and subsequent storming of the ship by nearby Venetian crews. Hundreds were killed and wounded. Only the direct intervention of Sebastiano Venier, the overall Venetian commander, prevented the conflict from spreading to more ships. The charismatic, energetic, tactful, but youthful 26 year old Don Juan was barely holding the coalition together. If the Turks refused to sail out and fight he didn’t think he could convince the Spanish to force the mouth of the Gulf of Corinth to engage the Turkish fleet sheltered in their well protected anchorage.

The next day, as his men searched Cephalonia, they found a single Cretan ship whose crew brought news from Cyprus: the fortress at Famagusta had fallen, and the island surrendered to the Turks. This was disconcerting for Don Juan, not because the island fell but because the relief of Cyprus was the raison d’etre of the expedition. The Spanish would surely depart.

That night, Don Juan called a council of war on his flagship, the Real (Re-Al, Spanish for “royal”) between his various commanders where he disclosed the news. The smaller Italian states, Naples, Sicily, Tuscany, Urbino, and Savoy all recognized they were next year’s target, and wanted to continue. The Papal commander, Marc Antonio Colonna, whose boss, Pope Pius V, went through so much trouble to assemble the coalition, of course wanted to attack, as did the Knights of Malta, whom had been at the forefront of the Crusade against the Ottoman Turks for nearly 300 years. But the Spanish were not the only concern of Don Juan’s: he also feared the loss of the Venetians. He thought that without Cyprus as an objective the Venetians would cut their losses. The Ottomans were their biggest trading partner, and this war was draining their coffers. Peace, even a bad peace, would return trade.

However, the Cretans also brought more disturbing news from Famagusta – the Venetian commander Antonio Bragadin was promised safe conduct for his men and the island’s Christian population if he surrendered, but once the gates were opened, the Turks, who lost 50,000 in the siege, turned on the defenders with a vengeance. The soldiers were killed, the civilians sold into slavery, and the officers tortured to death. Bragadin himself was flayed alive, his skin stuffed with straw, and along with the heads of his lieutenants, was displayed aloft on the Turkish flagship, Sultana. Venier, and his supremely competent second Agostino Barbarigo, demanded Turkish blood. The Spanish commander, the fiery veteran admiral Alvaro de Bazan recognized it was now a matter of honor, and threw his support into an attack. Only the wily Giovanni Andrea Doria from Genoa, on secret orders from King Philip II of Spain, advised caution.

Don Juan replied, “The time for advising is over, the time for fighting has begun.”

Doria, not wanting to be labeled a coward, disregarded Phillip’s instructions and agreed to attack.

You must be logged in to post a comment.