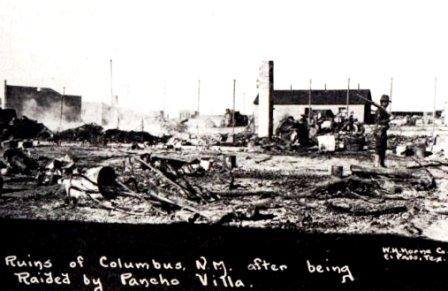

The Raid on Columbus

In the winter of 1915/16 Mexican counter-counter-revolutionary (I think), Pancho Villa, was on the losing end of his fight against “Primer Jefe” First Chief Venustiano Carranza. The “Villistas” as Pancho Villa and his men were called, were holed up in the Chihuahua Mountains and were desperate for supplies to continue. Three miles across the US/Mexican border was the town of Columbus, New Mexico, which could provide the necessary guns, horses, food, and blankets.

Before dawn on 9 March, 1916, Pancho Villa and 500 Villistas attacked Columbus and Camp Furlong just outside of town where 120 troopers of Headquarters, H, and F Troops of the 13th Cavalry were stationed. The garrison at Camp Furlong was saved by the actions of two lieutenants, one barefoot, who organized a defense around the post’s guard shack with the headquarters troop’s machinegun platoon. Once the Villistas were beaten back at the camp, F troop moved into Columbus where the civilians were fighting back from the brick schoolhouse while Pancho Villa and his men looted and burned the rest of the town. They arrived just in time to prevent the Villistas from robbing Columbus’ bank when a well-placed Hotchkiss machine gun prevented any attacker from crossing Broadway, Columbus’ main street.

The raid was successful, if at a heavy cost, as Pancho Villa stole hundreds of horses, rifles and pistols, and much needed food and blankets from the town at the cost 90 casualties, 70 of whom were killed. But he wasn’t counting on the natural aggressiveness of the United States Cavalryman. As Pancho Villa raced to the border, and then 15 miles into Mexico, the regimental executive officer with 40 men dogged them for the next 8 hours, killing or wounding another 250 Villistas, and forcing Pancho Villa to abandon much of his booty.

In the end Pancho Villa suffered over 300 casualties and the Americans eleven troopers and ten civilians killed and another dozen wounded in the Battle of Columbus. The raid sent shockwaves through the United States, particularity the death of the pregnant Mary James, who was killed by the Villistas fleeing the burning Hoover Hotel. President Wilson would authorize a punitive expedition into Mexico led by LTG John J. “Blackjack” Pershing to capture or kill Pancho Villa.

You must be logged in to post a comment.