Despite tenacious Italian resistance in the spring of 1941, swiftness of action, solid logistical planning, unconventional solutions, and engaged leadership allowed ad hoc and diverse Allied forces to reverse all of the Italian gains from the year before.

In the north, a large conventional invasion of Eritrea took place from the Sudan in November of 1940 led by the “Gazelle Force”, a mobile column used to conduct reconnaissance, raid, and screen the two division invasion force…kind of like an armored cavalry regiment. It took six months of hard fighting, and not a few setbacks, including a defeat or two, through well-fortified Italian positions before the Italians were routed at the Battle of Keren in late March. (Brig William Slim was wounded by a strafing Italian fighter during this advance).

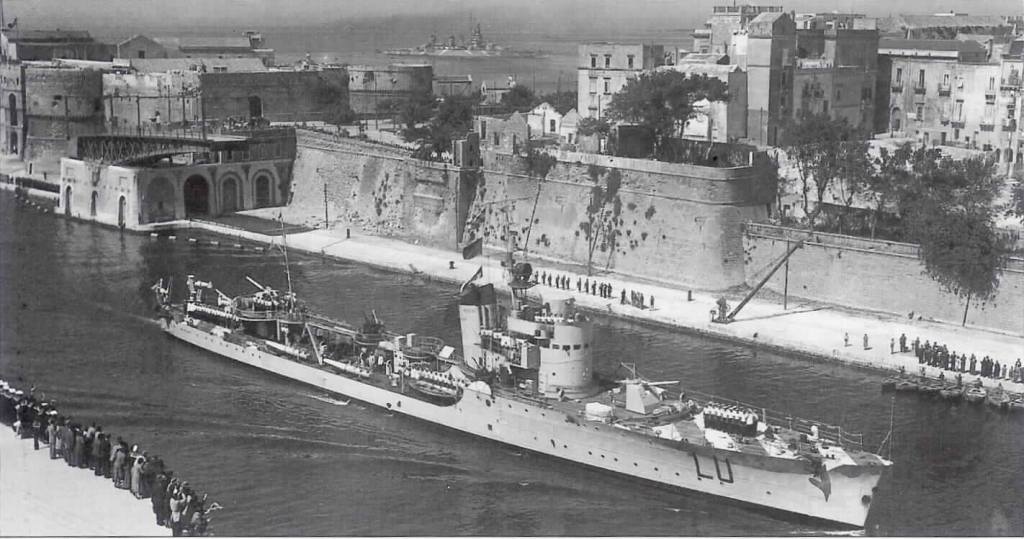

In the east, Sikhs, Punjabis, Baluchs, and Somali commandos of the 5th Indian Division landed at Berbera in March to recapture British Somaliland. It was the first Allied amphibious assault of the war. Berbera significantly cut down on supply difficulties of supporting from Kenya. After quickly defeating the surprised Italians, they reformed the Somali Camel Corps, and moved inland to meet the Africans moving up from Italian Somaliland.

In the south from his base in Kenya, Lieut Gen Cunningham, (Adm Cunningham’s little brother, funny “Howe” the Brits do that… I fukin kill me) split his command and invaded both Italian Somaliland and southern Ethiopia. Somaliland was seized thru a surprise joint and combined amphibious and land invasion into the teeth of an Italian defense that was expecting them. In the space of five months, the 11th (East) African Division, and the 12th (West) African Div, consisting of units from 14 different nations, arrived, organized, resourced, trained, planned, prepared, rehearsed, staged, and then coordinated a two prong attack into Italian Somaliland. (What can we do in five months?) They seized Mogadishu on 1 March and turned north into Ethiopia.

Cunningham’s other attack was a logistical nightmare across the barren and dry Chelbi Desert by the South African and Rhodesians, in coordination with the separate 8000 man Belgian “Force Publique” from the Congo. This attack went from the trackless desert of Chelbi to the jungles of the Ethiopian highlands at the height of the monsoon. Cunningham hoped to instigate an uprising, but southwest Ethiopia consisted of Ras (kingdoms) that were loyal to the Italians. This attack ended up fighting a brutal counterinsurgency as they moved toward Addis Ababa.

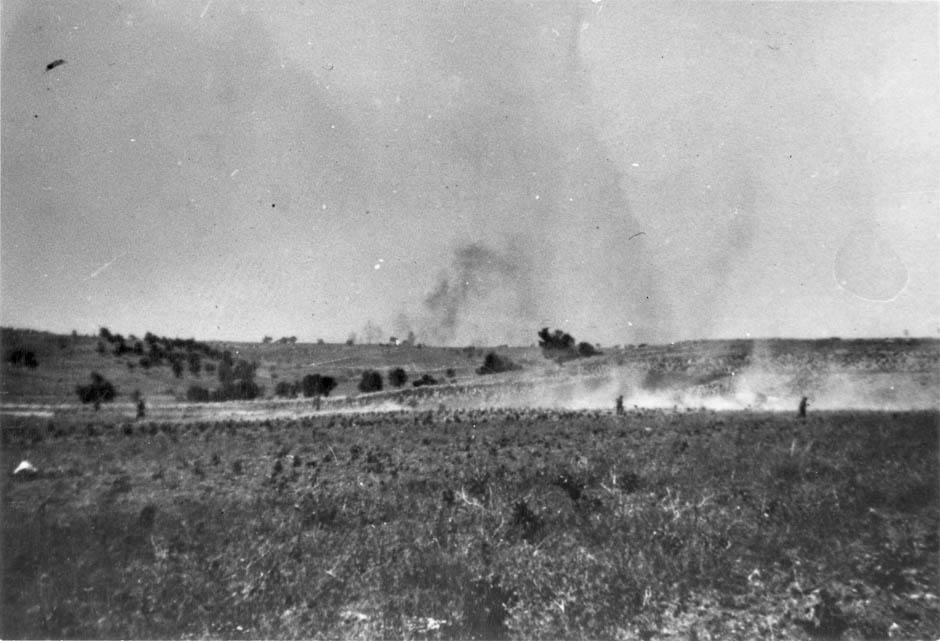

In the fight for Addis Ababa, the successes of Major Orde Wingate’s “Gideon Force” caused Ethiopian “Patriot” units to materialize all across the central, western, and northern parts of the country. The Italians, tied to their bases in the midst of a hostile population, had great difficulty massing on the Patriot units, and when they did, they were ambushed by the Gideon Force. The Italian commander of East Africa, the Duke of Aosta, feared the slaughter of Italian civilians in the capital, and retreated from the city in April.

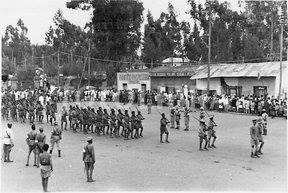

On 5 May 1941, Emperor Haile Selassie, the Ras Tafari and Lion of Judah, made a triumphant entry into Addis Ababa exactly five years after he was forced into exile by the Italians. He was escorted by his Patriots, and Orde Wingate and the Gideon Force. The Duke of Aosta retreated to Amba Algi but was encircled by Lieut Gen Platt (and Slim) from the north, and Cunningham from the south and east. Aosta would surrender 18 May.

Isolated Italian units would resist for another five months and a vicious insurgency would go on for years, but with the Italian defeat, five divisions of troops became available for operations elsewhere: Rommel was pushing on Egypt, the Australians were hard pressed holding Tobruk, Iraq was declaring war, Persia was leaning towards Germany, and the Japanese were threatening to occupy French Indochina, which threatened Burma, Malaya, Singapore, and India. The victory in Ethiopia was none too soon.

The successful East African campaign was the first victorious Allied land campaign of the war. The first Allied amphibious invasion of the war. And the first Axis territory liberated by the Allies in the war.

You must be logged in to post a comment.